Masonic Biographies

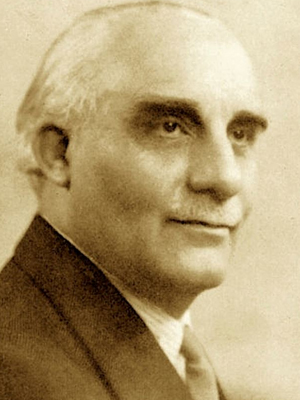

George Syndey Arundale

Born: Sunday, 01 December 1878

Died: Thursday, 12 July 1945

A dedicated servant of Humanity, George S. Arundale was an influential Theosophist and Freemason who helped to found Universal Co-Masonry and share the Light of Freemasonry across the world.

Each human being is born with some unique gift to bestow upon the world. Some are born to become great leaders: generals, politicians, explorers of the vast unknown. Bro. George S. Arundale may not be listed among these great Titans of History, but he was a true and dedicated servant of humanity. And it was through this noble, yet humble, calling – Service – that he endeavored to make his mark.

Few of us are unlucky enough to be born of tragedy; perhaps fewer still live to see that pain become a pillar of strength and fortitude later in life. Yet, this was how the story of Bro. George S. Arundale began. When George’s mother died from complications in childbirth, his father was so grief-stricken that he would not even look at his newborn son. Thus “orphaned” at birth, his Aunt, Miss Francesca Arundale, was given the responsibility of raising the boy. In the end, however, this mournful beginning evolved into a catalyst for expanded opportunity and development, which may have been unrealized by a child born into normal circumstances.

Few of us are unlucky enough to be born of tragedy; perhaps fewer still live to see that pain become a pillar of strength and fortitude later in life. Yet, this was how the story of Bro. George S. Arundale began. When George’s mother died from complications in childbirth, his father was so grief-stricken that he would not even look at his newborn son. Thus “orphaned” at birth, his Aunt, Miss Francesca Arundale, was given the responsibility of raising the boy. In the end, however, this mournful beginning evolved into a catalyst for expanded opportunity and development, which may have been unrealized by a child born into normal circumstances.

George’s Aunt and Adoptive Mother was a pioneer of her era – an influential English Theosophist and Freemason. Francesca joined the Theosophical Society in 1881; in 1895, Miss Arundale joined a French mixed Lodge. Elevated to the 33rd Degree, Francesca played a pivotal role in organizing what would become the Order of Universal Co-Masonry, encouraging Annie Besant to join the movement in 1902. A close friend of Besant and Helena Blavatsky, Francesca was highly regarded by the inner circle of influential early Theosophists. She frequently entertained the group at her Notting Hill House at 77 Elgin Circle, London.

Growing up surrounded by great philosophical minds, George followed in his Aunt’s footsteps in the Theosophical Society in 1895. The same year, Arundale commenced his higher education at St. John’s College, Cambridge, receiving the following degrees: BA (1898), LLB (1899), and MA (1902). After attending one of Annie Besant’s famous lectures in 1902, he was asked to work for her and assist in her important work and mission. He accompanied her and five other Theosophists to Paris in 1902 and was initiated into Freemasonry with her and other Theosophists. Fellow Co-Mason Esther Bright later wrote:

“Doctor Annie Besant became deeply interested in the possibility of starting a Co-Masonic movement in England in the summer of 1902… The next part of the plan was to set up a provisional Lodge at the Brights' home in London, to prepare for the founding of the first British Lodge. It is reported that a Provisional Lodge Meeting was held on 29th July 1902 when the seven founding members (those who had travelled to Paris) drew up and signed a petition for the Lodge to the Supreme Council. The name of the Lodge was to be The Scotch Symbolical Worshipful Lodge of England: Droit Humain, No.6 Human Duty.” - Miss Esther Bright, July 1947

(2).jpg) As a Co-Freemason, Bro. Arundale labored diligently for the Craft and Humanity for the rest of his life, eventually receiving the 33rd and Highest Degree of Freemasonry. In 1935, Arundale became Most Puissant Grand Commander of the Eastern Federation of the Order and Representative of the Supreme Council.

As a Co-Freemason, Bro. Arundale labored diligently for the Craft and Humanity for the rest of his life, eventually receiving the 33rd and Highest Degree of Freemasonry. In 1935, Arundale became Most Puissant Grand Commander of the Eastern Federation of the Order and Representative of the Supreme Council.

In 1903, at Dr. Besant’s invitation, Bro. Arundale, and his Aunt, moved to India, and he accepted a position as Professor of History at the Central Hindu College, Benares. In 1907, George was appointed Headmaster of the C. H. College School and later Principal of the College. After a brief period as General Secretary in England, Bro. Arundale returned to India to assist Dr. Besant in her political activities. With Theosophical support, a National University was founded in Madras, where Arundale joined the faculty and later received his Doctorate [D.Litt.]. In 1920, Mr. Arundale married Srimati Rukmini Devi, daughter of an important Theosophical Brahmin family and a gifted artist and dancer. Arundale became General Secretary in Australia in 1926, where, in addition to his Theosophical duties, he engaged in humanitarian and political work. He helped to establish the 2GB Broadcasting Station and became its first Chairman of Directors. Living at The Manor, Arundale assisted Bishop Leadbeater in his Theosophical work until he returned to India in 1928 at the request of his chief mentor, Dr. Besant. When she died in 1933, she bestowed upon him the great honor of naming George Arundale as her successor for President of the Theosophical Society. As B. Sanjiva Rao wrote in his Biography of George Arundale,

…surely there is no one in the world more devoted, more loyal to his beloved leader, than George S. Arundale. In his room at Shanti Kunja, Benares, there is a steel desk bearing the following inscription: "To George S. Arundale with love from A. B. in grateful recognition of a flawless devotion."

Thus, Dr. Arundale served as President of the Theosophical Society from 1934 until his death, shepherding the organization through the dark days of World War II and setting up a Peace and Reconstruction Department to draw up a Charter for World Peace when the War had ceased. Though he suffered from ill health in the later years of his tenure, he continued to preserve in his duties, both Theosophical and Masonic, traveling, writing, and supporting the institutions and activities with the support of his wife, Rukmini Devi. Throughout this period, Bro. Arundale wrote many books, including Mount Everest, Nirvana, Kundalini, and The Lotus Fire.

Thus, Dr. Arundale served as President of the Theosophical Society from 1934 until his death, shepherding the organization through the dark days of World War II and setting up a Peace and Reconstruction Department to draw up a Charter for World Peace when the War had ceased. Though he suffered from ill health in the later years of his tenure, he continued to preserve in his duties, both Theosophical and Masonic, traveling, writing, and supporting the institutions and activities with the support of his wife, Rukmini Devi. Throughout this period, Bro. Arundale wrote many books, including Mount Everest, Nirvana, Kundalini, and The Lotus Fire.

Diagnosed with Diabetes, he refused to treat his illness with insulin, which was only available then as derived from animals. A stanch Vegetarian in conviction, his did not allow for the sacrifice of another being’s life, even to save his own. Thus, he succumbed to his illness and passed to the Eternal Grand Lodge on July 4, 1945.

ROLES OF SERVICE

- President of the Theosophical Society: 1934-1945

- Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church: Consecrated July 4, 1925

MASONIC CAREER

- Initiated, Passed, and Raised in Paris, France (1902)

- Co-Founded and first Orator of Human Duty Lodge, No. 6; London, Universal Co-Masonry (Consecrated September 26, 1902)

- Co-Founded Dharma Lodge in Benares, India

- Co-Authored the “Dharma Ritual” (1904)

- District General Secretary of Universal Co-Masonry in India (1905)

- Most Puissant Grand Commander, Eastern Federation, and Representative of the Supreme Council (1935)

A FRAGMENT OF AUTOBIOGRAPHY

What a beautiful incarnation I have had this time. It began badly, for throughout my youth I was beset by serious ill-health; and it was not until my twenty first year that the evil, though, of course, just, karma from very long ago became exhausted.

.jpg) But very early in life, when quite a child, I met H. P. Blavatsky and loved her from the moment I saw her. Of course I could not understand her, at all events in my waking consciousness, but that mattered not at all. What mattered was my instinctive and intuitive love for her in my own childish way so far as regards the physical plane, but otherwise in that inner consciousness for which there was no room in the then outer court of my physical body.

But very early in life, when quite a child, I met H. P. Blavatsky and loved her from the moment I saw her. Of course I could not understand her, at all events in my waking consciousness, but that mattered not at all. What mattered was my instinctive and intuitive love for her in my own childish way so far as regards the physical plane, but otherwise in that inner consciousness for which there was no room in the then outer court of my physical body.

I also met, and came under the care of, that very great and very noble man, C. W. Leadbeater, whom naturally I could not appreciate in my childish body in terms of his true worth. And even when I grew a little older I was still unable to understand the veritable splendour of his living. I was a youth. And mine was a restless youth, eager to assert itself, impatient of guidance. Young as I was I felt I had a mission to discharge, though what it was I hardly knew, save that I must try to help poor people; and I had no idea how to set about it, save to try to find out from those poor people themselves whom I could come across what were their difficulties, what were their needs.

And I tried to do this by talking to poor people in London omnibuses, by stopping poor people in the London streets, and by wandering about their poor abodes. How differently my mission, such as it is, has turned out! I find I have no mission, but only the duty of trying to fit in as best I can where I am for the moment wanted.

In 1895 I became a member of the London Lodge of The Theosophical Society, Mr. A. P. Sinnett being then President of the Lodge. I rejoiced greatly in the affection of Mrs. Sinnett, and had much comradeship with their son Denny. Second only to my deep love for Miss Arundale and her noble mother Mrs. Arundale, who took care of me when my own mother died of puerperal fever, was my affection for Mrs. Sinnett.

I must confess that I found the meetings of this very fashionable Lodge intolerably dull, pompous, and most irritatingly authoritative, especially for one who knew he had wings and longed to fly, but who for the moment could not even flutter. I expect it was partly my stupidity and ignorance which caused me so to regard them, for I know now that much valuable understanding of Theosophy came from them. The fact remains that these meetings seemed to intensify my unfortunate, but, I hope, only temporary, inhibition in the matter of flying, and as I look back upon this round peg in a very square hole I am wondering whether, to our young members today, and for whatever reason, our own meetings seem as dull, as pompous, as irritatingly authoritative. Do we seem to be as uninspiring? Is there a tendency in us to lay down the law as if we alone knew the law? Do we seem to give little if any help to the young who know they have wings and who want to fly? Do we even tend to seem to clip their wings lest they begin to fly otherwise than ourselves? Perish the thought. Yet it happened in my young days. Why should it not happen now? I do sincerely believe that almost everywhere there are a few older Theosophists who would require the young Theosophists to crawl within already existing grooves, rather than to fly into the skies of their own new life.

I know very well that old people can be most wonderful, deeply inspiring, as young in their own way as the most virile youth. I know that they can be even more splendidly young than the young themselves. As witness Dr. Besant and Bishop Leadbeater themselves, and many others. But I know also that old people can be the reverse of wonderful, the reverse of inspiring. I know that they can become dull and static, and a veritable incubus to the young, of course with the very best intentions in the world.

I suffered in a way under the superiority complex on the part of many old people of my youth, and I am positively nervous lest young people of today be suffering under a superiority-complex on my part, though, of course, I shall be the first to deny that I have any such complex. There was something in the voices of these older people which seemed to ooze self-satisfaction and self-complacency, and a sense of quite definite omnipotence and omniscience, so far as young people were concerned. Is it the Fame now? Does my voice similarly ooze? I sometimes am appalled to think that perhaps it does as I listen to myself over the radio or from a gramophone record. But God forbid this should be so in fact.

Shortly after my joining The Society--now forty-five years ago--I went to Cambridge University where I did not distinguish myself at all, but managed to acquire the degrees which would in after life deceive the general public into the belief that I am an educated man, and thus enable me to take up that educational career for which I was in fact rather more fitted than might be thought.

Then came a period of pralaya during the course of which I nearly did many things, but not quite. I nearly became a solicitor, but not quite. I nearly became a journalist, but not quite. I nearly joined the staff of the London Daily Mail, but not quite.

Then came a period of pralaya during the course of which I nearly did many things, but not quite. I nearly became a solicitor, but not quite. I nearly became a journalist, but not quite. I nearly joined the staff of the London Daily Mail, but not quite.

Evidently, I was waiting for something, or rather my ego was waiting for something. And that something came in the person of Mrs. Annie Besant; as she then was, to whom I was introduced at the Queen’s Hall shortly after I had settled down to office work at the headquarters of the then British Section in Albemarle Street, London.

As I am never tired of saying--she came, I saw, she conquered: for I knew at once, the moment I saw her, that it was she for whom I had been waiting, and that my future life would I be inextricably interwoven with hers, praise be to God!

I believe she also knew that one of her old servants had come before her and would rejoin her staff in this life as he had been a member of it in lives gone by. I could not, of course, see much of her. for I was nobody in particular, and she was everybody in general. But the sight of her changed my life, and whenever there was anything I could do to help her I was all excitement to do it.

When she established the British Empire division of the great Masonic movement which admitted women to its ranks, having its headquarters in Paris, with those heroic dynamos, Maria Deraismes and the Georges Martins, as its chieftains, there I was to help in my small way, with my aunt, Miss Arundale, who was the real link between Mrs. Besant and the French organisation; and I can well remember how in 1902 I entirely devoted myself at our house in Epling, near London to the work of helping to build the foundations of Co-Freemasonry in the British Empire. It was Miss Arundale who, herself already a Co-Freemason, brought Mrs. Besant into touch with the French Supreme Council. And a small body of us went over to Paris to become full-fledged Co-Freemasons.

Thus did I gradually draw closer and closer to my old leader, and towards the end of the same year it was she who asked my aunt and myself to transfer ourselves to India to work with her there. So we did in the beginning of 1903, to our immense advantage. I had already one Motherland, Britain; I now acquired another, India. And today I do not know which I love most. India is the greater land, of course, but Britain has her own unique splendour, and as I watch her facing the foe with calm courage, lightheartedly,” indomitably set to win, my heart thrills with pride, and I thank God that I am blessed with two Motherlands, one of the East and the other of the West, not with one alone, and each shining as a sparkling star in the firmament of my being. How much brighter is my life with two stars in its sky!

Then some delightful years in Benares, with so many wonderful friends and so much wonderful work, and so near to my leader. How inspiring it was to watch Mrs. Besant at work, ennobling everything she touched, vivifying magically every person and every activity with which she came into contact, living even in the very little things of life the life of a hero, nay, the life of a God, What tremendous influence she wielded over her vast family of the Central Hindu College and the Central Hindu Girls School. And what a power she was, before whom even the autocrats trembled in the political field, as she threw herself into the high purpose of India’s regeneration in every department of the age-old nation’s life!

I think I grew during these years from 1903 to 1913 as perhaps I have not grown since, for she breathed forth a scintillating example which one could do no other than emulate in some small degree. Almost despite myself I became changed, as did we all. How fortunate we were to be living in such times as those, when there was not a single individual, even if only remotely in touch with her, who had not the opportunity to compress decades of unfoldment within the compass of one single year.

I think I grew during these years from 1903 to 1913 as perhaps I have not grown since, for she breathed forth a scintillating example which one could do no other than emulate in some small degree. Almost despite myself I became changed, as did we all. How fortunate we were to be living in such times as those, when there was not a single individual, even if only remotely in touch with her, who had not the opportunity to compress decades of unfoldment within the compass of one single year.

Indeed did she fashion us in her likeness. Not that we became like her. That would have been impossible. But that we became more like our real selves, through becoming imbued with her spirit to the measure of our receptivity. We were all comparatively small vessels. Yet could she change us, widen us, and she did. She was so perfectly real, and thus drew each one of us closer to his own reality.

It was towards the close of my life in the Central Hindu College at Benares--I hope I helped her more than I hindered her, but young people do so often make mistakes tiresome to their leaders, though she never complained--God bless her that I renewed my close association with C. W. Leadbeater, and through him and Mrs. Besant came into contact with J. Krishnamurti and his wonderful brother J. Nityananda. How I loved, and still love, these two dear people, though Nityananda has passed onwards, and Krishnamurti has his own great work to do far different from the little work that I can do.

I am thankful that in these later and more discerning years I renewed my apprenticeship under C. W. Leadbeater. I then came to know of his greatness, of his humility, of his constant joyousness, of his abiding affection seeking no return, and of his complete indifference to, and entire absence of resentment of, the torrent of persecution which fastened upon him through the machinations of those who were steeped in narrow, cold self-righteousness. My blood boiled then, and it still boils now, as I remember the way in which the modern counterparts of the medieval inquisition fastened upon him with their utterly evil insinuations, these being as false, of course, as were the natures of those who spread them abroad. C. W. Leadbeater was a very noble, a very wise, and a very saintly man, and he was crucified for precisely the same reasons as our Lord was crucified--his greatness, the fact that he towered infinitely above all his fellows, was intolerable to the pygmies who sought to reduce him to their own vulgar and unsavoury level. But enough of this. He was ever untouched by the filth with which they sought to bespatter him, and they will meet their deserts in due course.

I think of one of the happiest times in my life, apart from being with H. P. Blavatsky, and later with C W. Leadbeater, which were happenings I could not then realize, as now I realize them, as being when I first met Mrs. Besant in this particular incarnation. The second was when Miss Arundale and I worked under her in the Central Hindu College, surrounded by so many friends, young and old. The third was my meeting beloved C. W. Leadbeater for the second time in this life. The fourth was my renewing from long ago my close friendship with Krishna and Nitya as I grew to call them.

I think of one of the happiest times in my life, apart from being with H. P. Blavatsky, and later with C W. Leadbeater, which were happenings I could not then realize, as now I realize them, as being when I first met Mrs. Besant in this particular incarnation. The second was when Miss Arundale and I worked under her in the Central Hindu College, surrounded by so many friends, young and old. The third was my meeting beloved C. W. Leadbeater for the second time in this life. The fourth was my renewing from long ago my close friendship with Krishna and Nitya as I grew to call them.

What happy times we had at Adyar during the holidays when I was able to get away from my duties as Principal of the Central Hindu College. How I reverenced the mighty young man who shed about him so fragrant an aura of deep spirituality. And how I loved him, too. How we enjoyed being together. What happy times we had in Europe, and especially in Taormina, Sicily. They were glorious times while they lasted. At the time I thought they would go on for ever, and so I think did he and Nitya. But the time came when our ways had to part. The time came when he had to go his way and I had to go mine, for to him was allotted a mission the nature of which he himself alone knows; and I had my little jobs to do. I wonder if he still remembers me, for he has so much to live in the Eternal, so little in time. And, alas, dear Nitya was unable to remain with his brother, for tuberculosis claimed his frail young body, and a link in this incarnation was broken which, had it been retained, might, I think, have substantially changed all that has actually happened. Two great souls they are, and I pay utmost homage to that greatness even as from time to time, in the pursuance of what I feel to be my duty, I differ radically from some of Krishnaji’s pronouncements.

But what do these differences matter? He has his word to speak, and I, in humbler measure, have mine.

The fifth most happy time was when, once more under Mrs. Besant, I plunged into the political life of India, raw recruit though she must have found me as compared with many other of her subordinates. But at least I had enthusiasm, and I gave it to the full. I do not think I have enjoyed any work more than helping to organise The Home Rule for India League, and to betake myself every day to the offices of Mrs. Besant’s daily newspaper New India, to function as a sub-editor and general factotum.

I felt such a fighter, and I found that I could speak sufficiently well to hold an audience. I revelled in it all. And when the foolish order of internment came upon Mrs. Besant, Mr. Wadia and myself, I felt lifted into the seventh heaven of delight. I believe this so-called martyrdom was considered to be a splendid Advertisement for Home Rule. No doubt it was. But what I cared for was the exhilaration of it all, though its effect upon Mrs. Besant was dangerously the reverse. It nearly killed her, as I can now well see why. But it made me laugh, nor I was not the general, only a private in her army who was privileged to take the stage awhile with her. Of course I laughed, for I had suddenly become a peacock when in fact I was only a crow. I enjoyed a vicarious at-one-ment with my chief which lifted me into otherwise unattainable regions, and I drew in deep breaths of a vitality-laden air.

Then came along some years later, in 1920, my sixth most happy time, which still continues, I am thankful to say my meeting, again for the first time in this life, with Rukmini, or should I say more respectfully, Shrimati Rukmini Devi.

As I look back I see how justified I am in writing of this incarnation as being “beautiful,” and how thankful I ought to be, and I think I am, as its evening steals over me, for such happy times and for so comparatively an unclouded sky. I will not deny that I have had my trials and tribulations, nor that here and there have I been crucified. Such is the case with all. But without the experience of darkness there can be little appreciation of light. Without troubles and sorrows there can neither be conquests nor delights. Without storms there cannot be peace. And as I look back I feel thrilled by the wonderful karma that has blessed me through so many of my sixty-odd years.

What astonishes me in a special degree is how, as the little Arundale planet revolves around the central Sun of Life, it is continually entering the orbits of Stars of major brilliance. And these stars are not film stars but Stars of Life—H. P. Blavatsky, the first of them; C W. Leadbeater the second of them; Annie Besant, the third of them; Krishnamurti and Nityananda, the fourth and fifth of them; and then Rukmini, the sixth of them. And who knows whether, during the years remaining to me, there may not be other similarly starlit orbits through which this small planet of mine shall pass.

I am not counting those stars of somewhat lesser magnitude which I may have encountered in the outer world. I have met many people whom the world counts as great in the ordinary sense of greatness. But above all I cherish these major Stars, six of which I have enumerated, Stars which are counted great in the inner worlds, and all of which, as it happens, are also counted great in the less discerning outer world itself.

I am not counting those stars of somewhat lesser magnitude which I may have encountered in the outer world. I have met many people whom the world counts as great in the ordinary sense of greatness. But above all I cherish these major Stars, six of which I have enumerated, Stars which are counted great in the inner worlds, and all of which, as it happens, are also counted great in the less discerning outer world itself.

I think I might well have added one or two other Stars of brilliance in the same category of having an imprimatur from the inner standards. Certainly, H. S. Olcott, the great President-Founder of our Society, whose mighty work has earned for him undying fame. But he did not affect me as profoundly in the outer world, nor in the inner worlds, as have those whom I may well call the great six of my life.

Then there was that wonderful personage, Sir S. Subramania Iyer, late Acting Chief Justice of the High Court of Madras and Vice-President of The Theosophical Society. A very noble being was this great ascetic and most learned gentleman, and a tower of strength to the Theosophical movement throughout the world. But I did not know him very well, or I am sure he would have been the seventh of my Stars.

Another Star of no less magnitude is C. Jinarajadasa, whose learning and deep understanding bring him at once into the front rank of the spiritually eminent. His services to Theosophy and to its channel-movement through, I believe, nearly, or possibly more than, half a century of years, have helped to give it a strength which has served it in great stead during the critical years which have fallen to its lot. I remember that he and I were fellow-students together at Cambridge. But his work and my own have lain in such different channels that we have had to work apart more than together, and I have on the whole seen less of him than of those who have more profoundly affected my life with their immediate radiance. But I have indeed to be grateful to him for his unstinted support during my term of office as President since 1934, and for his affectionate and tolerant understanding.

But let me now return to my sixth Star Rukmini. Words quite fail me to describe my joy in the beauty of her character no less than in the beauty of her physical form. It is curious, and intensely stupid, how one is supposed not to praise in public members of one’s own family. It is curious and it is stupid because there is really far more true worth in one member’s appreciation of another member than in the appreciation of a stranger. There may be a little personal prejudice involved. But the most natural life an individual leads is generally in the bosom of his family, day by day in the innumerable circumstances that come to test the carat-value of his qualities and weaknesses in their daily reaction to the pinpricks of domesticity.

I make, therefore, no apology for bearing what I regard as an entirely unbiassed, eager and most grateful testimony to the beauty which radiates from Rukmini, and I know that there are very many others whose testimony will be no less wholehearted. I only wish I could have made her life as worthwhile and as happy as she has made mine, and when I am no longer wearing this particular physical garment she will, I most earnestly trust, have the beautiful memory that she made smooth and joyous my ways.

I make, therefore, no apology for bearing what I regard as an entirely unbiassed, eager and most grateful testimony to the beauty which radiates from Rukmini, and I know that there are very many others whose testimony will be no less wholehearted. I only wish I could have made her life as worthwhile and as happy as she has made mine, and when I am no longer wearing this particular physical garment she will, I most earnestly trust, have the beautiful memory that she made smooth and joyous my ways.

It was not until fourteen years later that I embarked on what was to be in fact my seventh happiness—a happiness different from all the other six--that of succeeding my beloved spiritual mother as President of The Theosophical Society. The happiness was not in becoming President, great though the honour was and is. To be President is to have the most arduous work and a sense of the gravest responsibility, with the knowledge that it is impossible to please everybody. The seventh happiness consisted rather in feeling that I had been considered worthy to follow in her footsteps, at however great a distance, than in some sense of achieving anything particularly useful.

It consisted in feeling deeply privileged in being allowed to try here and there, but, of course, only here and there, to carry on her work, and to stand up to bear witness to the glory of the unending mission in which she has been engaged life after life from long ago, and to its mighty majesty. I feel that I may here, in a very small way, bear testimony to the fact which I know to be true that she works now and today out of the body as she worked when in it, and that she is the great leader, the great statesman, the great warrior, the great mother, the great friend, the great Yogi, that she ever has been.

I do not know if I shall be called upon to enter upon a second term. I am thankful enough for the first. This one step has been enough for me. Very well and very good if another is called to take my place. But if I am called to do my best for another seven years, I shall still feel that I can do no better than to represent her in the best way I can, ever remembering those who stand behind her.

Stringing together all these seven happinesses and making them and this incarnation of mine still more beautiful has been the golden cord of the precious happiness constantly to rejoice in the friendship, the stalwart support, the affection, the ceaseless understanding, of many, many friends throughout the world. How fortunate am I in this! Everywhere I go I make new and everlasting friendships, and I renew old ones the friendships of those who have been dear to me, and to whom I am dear, from long ago, and who will be my friends forever.

How many friends I have; friends who are often thinking of me in all parts of the world and of whom I am constantly thinking, too. And how I rejoice in their unwavering understanding, in their helpfulness, in their graciousness and forbearance. Naught can ever dim, still less break, such a friendship as they have with me and I with them, a friendship which everything, no matter what it may be, can only strengthen, even if it be a temporary separation, a fleeting misunderstanding. In my friendships it is the friendship which is everlasting, and all that constitutes it: all else comes and goes impermanent.

So far as I am concerned, I never lose a friend. I look back through the whole of my life, and I can say in perfect truth that all with whom I have ever had friendship are still my friends, and will always be my friends, however much there may be, for the time being, clouds to ‘divide us. Friendship is more precious to me than differences of opinion, divergencies of work, or disapproval in all its degrees; and the friendships I have collected I keep.

I am always adding, and never subtracting, friends. Even if they depart from me, so far as they are concerned, I do not depart from them. It may be that the cause of the departure is my fault or it may be theirs. But my own faults will pass away, as also will theirs, and the sunshine of friendship will someday shine forever unclouded by the mutual ignorance of these earlier times of separativeness. This sunshine is shining even when it seems to have ceased to shine. Only our stupidity and ignorance cause us to think it is not there. It is not the Sun of Friendship that ever sets, but we who set awhile to it.

How grateful I am to all my friends for the rich happiness and strength their friendship brings to me. Some of them may think that I give them more than they give me. But it is not so. Friendship is just friendship, and all comparisons are unworthy of one of the most beautiful of relationships. To give and to receive friendship--this is the Brotherhood which is already Universal in fact, but which we all have still to know and to experience as Universal. The glory of life is summed up in the words: I am your friend and you are mine.

And this brings me to the supreme happiness which has glorified all the others--my personal knowledge of the existence of the Elder Brethren and of more than one of Them in particular.

When I was very young I had the priceless privilege of being under the guardianship of the Master K. H., and all through my life He has watched over me with His own exquisite care. In the early days of childhood and my youth I needed this care to help me through the payment of the debts I owed as the result of living not too wisely in the past. In 1910 I was privileged to draw close to Him as one of His junior pupils or apprentices, and from that time forward I have been privileged to receive the gracious guidance of more than one of the Elder Brethren. I cannot go into details, for these matters are sacred and to be treasured secretly in the heart.

But the personal knowledge of Them! How infinitely precious and overwhelmingly heartening! Without Them, and without the splendid light and warmth of the Stars and friends of my life, I could not have done even the little I may have done. But with Them, with the light and warmth of my beloved and revered friends and comrades--if I may so call those whose lives are so much more beautiful than my own, and with the splendid galaxy of my friends all over the world, I hope I have been helpful in some measure, as I have been most happy, in this beautiful incarnation, than which I can conceive no incarnation more blessed.