Masonic, Occult and Esoteric Online Library

Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt

By James Henry Breasted

Popularization of the Old Royal Hereafter—Triumph of Osiris—Conscience and the Book of the Dead—Magic and Morals

The scepticism toward preparations for the hereafter involving a massive tomb and elaborate mortuary furniture, the pessimistic recognition of the futility of material equipment for the dead, pronounced as we have seen these tendencies to be in the Feudal Age, were, nevertheless, but an eddy in the broad current of Egyptian life. These tendencies were undoubtedly the accompaniment of unrelieved pessimism and hopelessness, on the one hand, as well as of a growing belief in the necessity of moral worthiness in the hereafter, on the other; they were revolutionary views which did not carry with them any large body of the Egyptian people. As the felicity of the departed was democratized, the common people took up and continued the old mortuary usages, and the development and elaboration of such customs went on without heeding the eloquent silence and desolation that reigned on the pyramid plateau and in the cemeteries of the fathers. Even Ipuwer had said to the king: "It is, moreover, good when the hands of men build pyramids, lakes are dug, and groves of sycomores of the gods are planted." 1 In the opinion of the prosperous official class the loss of the tomb was the direst possible consequence of unfaithfulness to the king, and a wise man said to his children:

"There is no tomb for one hostile to his majesty;

But his body shall be thrown to the waters."

By the many, tomb-building was resumed and carried on as of old. To be sure, the kings no longer held such absolute control of the state that they could make it but a highly organized agency for the construction of the gigantic royal tomb; but the official class in charge of such work did not hesitate to compare it with Gizeh itself. Meri, an architect of Sesostris I, displays noticeable satisfaction in recording that he was commissioned by the king "to execute for him an eternal seat, greater in name than Rosta (Gizeh) and more excellent in appointments than any place, the excellent district of the gods. Its columns pierced heaven; the lake which was dug reached the river, the gates, towering heavenward, were of limestone of Troja. Osiris, First of the Westerners, rejoiced over all the monuments of my lord (the king). I myself rejoiced and my heart was glad at that which I had executed." 2 The "eternal seat" is the king's tomb, including, as the description shows, also the chapel or mortuary temple in front.

While the tombs of the feudal nobles not grouped about the royal pyramid, as had been those of the administrative nobles of the Pyramid Age, were now scattered in the baronies throughout the land, they continued to enjoy to some extent the mortuary largesses of the royal treasury. The familiar formula, "an offering which the king gives," so common in the tombs about the pyramids, is still frequent in the tombs of the nobles. It is, however, no longer confined to such tombs. With the wide popularization of the highly developed mortuary faith of the upper classes it had become conventional custom for every man to pray for a share in royal mortuary bounty, and all classes of society, down to the humblest craftsman buried in the Abydos cemetery, pray for "an offering which the king gives," although it was out of the question that the masses of the population should enjoy any such privilege.

It is not until this Feudal Age that we gain any full impression of the picturesque customs connected with the dead, the observance of which was now so deeply rooted in the life of the people. The tombs still surviving in the baronies of Upper Egypt have preserved some memorials of the daily and customary, as well as of the ceremonial and festival, usages with which the people thought to brighten and render more attractive the life of those who had passed on. We find the same precautions taken by the nobles which we observed in the Pyramid Age.

The rich noble Hepzefi of Siut, who flourished in the twentieth century before Christ, had before death erected a statue of himself in both the leading temples of his city, that is, one in the temple of Upwawet, an ancient Wolf-god of the place, from which it later received its name, Lycopolis, at the hands of the Greeks, and the other in the temple of Anubis, a well-known Dog- or Jackal-god, once one of the mortuary rivals of Osiris. The temple of Upwawet was in the midst of the town, while that of Anubis was farther out on the outskirts of the necropolis, at the foot of the cliff, some distance up the face of which Hepzefi had excavated his imposing cliff tomb. In this tomb likewise he had placed a third statue of himself, under charge of his mortuary priest. He had but one priest for the care of his tomb and the ceremonies which he wished to have celebrated on his behalf; but he had secured assistance for this man by calling in the occasional services of the priesthoods of both temples, and certain of the necropolis officials, with all of whom he had made contracts, as well as with his mortuary priest, stipulating exactly what they were to do, and what they were to receive from the noble's revenues in payment for their services or their oblations, regularly and periodically, after the noble's death.

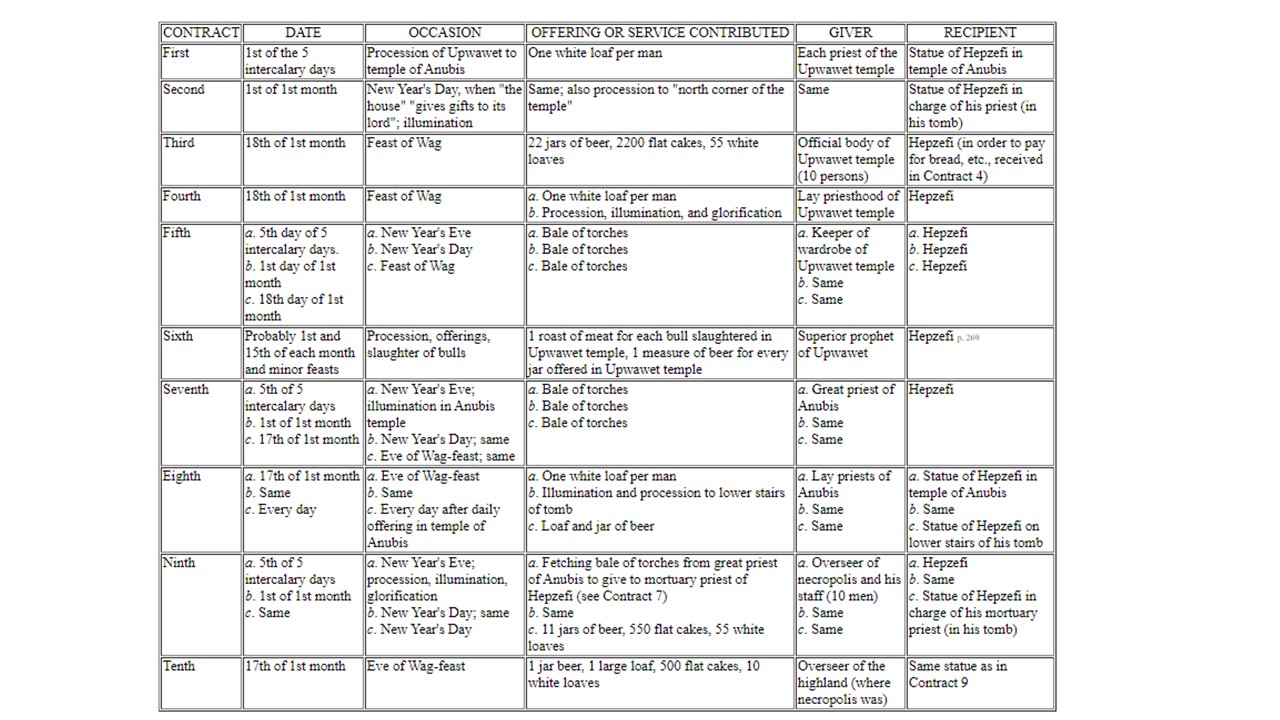

These contracts, ten in number, were placed by the noble in bold inscriptions on the inner wall of his tomb-chapel, and they furnish to-day a very suggestive picture of the calendar of feasts celebrated in this provincial city of which Hepzefi was lord—feasts in all of which living and dead alike participated. The bald data from these contracts will be found in a table below (pp. 268–9), and on the basis of these the following imaginative reconstruction endeavors to correlate them with the life which they suggest. The most important celebrations were those which took place in connection with the new year, before its advent, as well as at and after its arrival. They began five days before the end of the old year, on the first of the five intercalary days with which the year ended. On this day we might have seen the priests of Upwawet in procession winding through the streets and bazaars of Siut, and issuing at last back of the town as they conducted their god to the temple of Anubis at the foot of the cemetery cliff. Here a bull was slaughtered for the visiting deity. Each of the priests carried in his hand a large conical white loaf of bread, and as they entered the court of the Anubis temple, each deposited his loaf at the base of Hepzefi's statue.

Five days later, as the day declined, the overseer of the necropolis, followed by the nine men of his staff, climbed down from the cliffs, past many an open tomb-door which it was the duty of these men to guard, and entered the shades of the town below, now quite dark as it lay in the shadow of the lofty cliffs that overhung it. It is New Year's Eve, and in the twilight here and there the lights of the festival illumination begin to appear in doors and windows. As the men push on through the narrow streets in the outskirts of the town, they are suddenly confronted by the high enclosure wall of the temple of Anubis. Entering at the tall gate they inquire for the "great priest," who presently delivers to them a bale of torches. With these they return, slowly rising above the town as they climb the cliff again. As they look out over the dark roofs shrouded in deep shadows, they discover two isolated clusters of lights, one just below them, the other far out in the town, like two twinkling islands of radiance in a sea of blackness which stretches away at their feet. They are the courts of the two temples, where the illumination is now in full progress. Hepzefi, their ancient lord, sleeping high above them in his cliff tomb, is, nevertheless, present yonder in the midst of the joy and festivity which fill the temple courts. Through the eyes of his statue rising above the multitude which now throngs those courts, he rejoices in the beauty of the bright colonnades, he revels, like his friends below, in the sense of prodigal plenty spread out before him, as he beholds the offering loaves arrayed at his feet, where we saw the priests depositing them; and his ears are filled with the roar of a thousand voices as the rejoicings of the assembled city, gathered in their temples to watch the old year die and to hail the new year, swell like the sound of the sea far over the dark roofs, till its dying tide reaches the ears of our group of cemetery guards high up in the darkness of the cliffs as they stand silently looking out over the town.

Just above is the great façade of the tomb where their departed lord, Hepzefi, lies. The older men of the party remember him well, and recall the generosity which they often enjoyed at his hands; but their juniors, to whom he is but an empty name, respond but slowly and reluctantly to the admonitions of the gray-beards to hasten with the illumination of the tomb, as they hear the voice of Hepzefi's priest calling upon them from above to delay no longer. The sparks flash from the "friction lighter" for an instant and then the first torch blazes up, from which the others are quickly kindled. The procession passes out around a vast promontory of the cliff and then turns in again to the tall tomb door, where Hepzefi's priest stands awaiting them, and without more delay they enter the great chapel. The flickering light of the torches falls fitfully upon the wall, where gigantic figures of the dead lord rise so high from the floor that his head is lost in the gloom far above the waning light of the torches. He seems to admonish them to punctilious fulfilment of their duties toward him, as prescribed in the ten contracts recorded on the same wall. He is clad in splendid raiment, and he leans at ease upon his staff. Many a time the older men of the group have seen him standing so, delivering judgment as the culprits were dragged through the door of his busy bureau between a double line of obsequious bailiffs; or again watching the progress of an important irrigation canal which was to open some new field to cultivation. Involuntarily they drop in obeisance before his imposing figure, like the scribes and artisans, craftsmen and peasants who fill the walls before him, in gayly colored reliefs vividly portraying all the industries and pastimes of Hepzefi's great estates and forming a miniature world, where the departed noble, entering his chapel, beholds himself again moving among the scenes and pleasures of the provincial life in which he was so great a figure. To him the walls seem suddenly to have expanded to include harvest-field and busy bazaar, workshop and ship-yard, the hunting-marshes and the banquet-hall, with all of which the sculptor and the painter have peopled these walls till they are indeed alive.

The torches are now planted around the offerings, thickly covering a large stone offering-table, behind which sits Hepzefi's statue in a niche in the wall; and then the little group slowly withdraws, casting many a furtive glance at a false door in the rear wall of the chapel, through which they know Hepzefi may at any moment issue from the shadow world behind it, to re-enter this world and to celebrate with his surviving friends the festivities of New Year's Eve.

The next day, the first day of the new year, is the greatest feast-day in the calendar. There is joyful exchange of gifts, and the people of the estate appear with presents for the lord of the manor. Hepzefi's descendants are much absorbed in their own pleasure, but his cautious contracts, as still recorded in the town archives, ensure him from neglect. While the peasants and the leaseholders of the barony are crowding the gates of the manor-house, bringing in their gifts to their living lord and thinking little, if at all, of his departed predecessor, we discover the little knot of ten necropolis guards, headed by their chief, again entering the outskirts of the town and proceeding to one of the treasuries of the estate where they are entitled to draw supplies. Presently they march away again, bearing five hundred and fifty flat cakes, fifty-five white loaves, and eleven jars of beer. Pushing their way slowly through the holiday crowds they retrace their steps to the entrance of the cemetery at the foot of the cliffs, where they find a large crowd already gathered, every one among them similarly laden. Amid much shouting and merry-making, amid innumerable picturesque scenes of Oriental folk-life, such as are still common in the Mohammedan cemeteries of Egypt at the Feast of Bairam, the good towns-people of Siut carry their gifts of food and drink up the cliff to the numerous doors which honeycomb its face, that their dead may share the joyous feast with them. It is, indeed, the earliest Feast of All-Souls. The necropolis guards hasten up to Hepzefi's chapel with their supplies, which they quickly deliver to his priest, and are off again to preserve order among the merry crowds now everywhere pushing up the cliff.

As the day wears on there are busy preparations for the evening celebration, for the illumination, and the "glorification of the blessed," who are the dead. The necropolis guards, weary with a long day of arduous duty in the crowded cemetery, descend for the second time into the town to the temple of Upwawet. Here they find the entire priesthood of the temple waiting to receive them. At the head of the line the "great priest" delivers to the ten guards of the necropolis the torches for Hepzefi's "illumination." These are quickly kindled from those which the priests already carry, and the procession of guards and priests together moves slowly out of the temple court and across the sacred enclosure "to the northern corner of the temple," as the contract with Hepzefi prescribes, chanting the "glorification" of Hepzefi. 1 As they go the priests carry each a large conical loaf of white bread, such as they had laid before the statue of Hepzefi in the temple of Anubis five days before. Arrived at the "northern corner of the temple," the priests turn back to their duties in the crowded sanctuary, doubtless handing over their loaves to the necropolis guards, for, as stipulated, these loaves were destined for the statue of Hepzefi in his tomb. Threading the brightly lighted streets of the town, the little procession of ten guards pushes its way with considerable difficulty through the throngs, passing at length the gate of the Anubis temple, where the illumination is in full progress, and the statue of Hepzefi is not forgotten. As they emerge from the town again, still much hampered by the crowds likewise making their way in the same direction, the dark face of the cliff rising high above them is dotted here and there with tiny beacons moving slowly upward. These are the torches of the earlier townspeople, who have already reached the cemetery to plant them before the statues and burial-places of their dead. The guards climb to Hepzefi's tomb as they had done the night before and deliver torches and white bread to Hepzefi's waiting priest. Thus the dead noble shares in the festivities of the New Year's celebration as his children and former subjects were doing.

Seventeen days later, on the eve of the Wag-feast, the "great priest of Anubis" brought forth a bale of torches, and, heading his colleagues, they "illuminated" the statue of Hepzefi in the temple court, while each one of them at the same time laid a large white loaf at the feet of the statue. The procession then passed out of the temple enclosure and wound through the streets chanting the "glorification" of Hepzefi till they reached another statue of him which stood at the foot of the stairs leading up the cliff to his tomb. Here they found the chief of the desert patrol, or "overseer of the highland," where the necropolis was, just returning from the magazines in the town, having brought a jar of beer, a large loaf, five hundred flat cakes, and ten white loaves to be delivered to Hepzefi's priest at the tomb above. The next day, the eighteenth of the first month, the day of the Wag-feast, the priests of Upwawet in the town each presented the usual large white loaf at Hepzefi's statue in their temple, followed by an "illumination" and "glorification" as they marched in procession around the temple court.

Besides these great feasts which were thus enjoyed by the dead lord, he was not forgotten on any of the periodic minor feasts which fell on the first of every month and half-month, or on any "day of a procession." On these days he received a certain proportion of the meat and beer offered in the temple of Upwawet. His daily needs were met by the laymen serving in successive shifts in the temple of Anubis. As this sanctuary was near the cemetery, these men, after completing their duties in the temple, went out every day with a portion of bread and a jar of beer, which they deposited before the statue of Hepzefi "which is on the lower stairs of his tomb." There was, therefore, not a day in the year when Hepzefi failed to receive the food and drink necessary for his maintenance.

Khnumhotep, the powerful baron of Benihasan, tells us more briefly of similar precautions which he took before his death. "I adorned the houses of the kas and the dwelling thereof; I followed my statues to the temple; I devoted for them their offerings: the bread, beer, water, wine, incense, and joints of beef credited to the mortuary priest. I endowed him with fields and peasants; I commanded the mortuary offering of bread, beer, oxen, and geese at every feast of the necropolis: at the Feast of the First of the Year, of New Year's Day, of the Great Year, of the Little Year, of the Last of the Year, the Great Feast, at the Great Rekeh, at the Little Rekeh, at the Feast of the Five (intercalary) Days on the Year, at ⌈. . .⌉ the Twelve Monthly Feasts, at the Twelve Mid-monthly

Note.—The "bale of torches" above enumerated is an interpretation of the word "gm?t," which I rendered "wick" in my Ancient Records, following Erman (ÄZ, 1882, pp. 159–184).

Feasts; every feast of the happy living and of the dead. 1 Now, as for the mortuary priest, or any person who shall disturb them, he shall not survive, his son shall not survive in his place." 2 The apprehension of the noble is evident, and such apprehensions are common in documents of this nature. We have seen Hepzefi equally apprehensive.

That these gifts to the dead noble should continue indefinitely was, of course, quite impossible. We of to-day have little piety for the grave of a departed grandfather; few of us even know where our great-grandfathers are interred. The priests of Anubis and Upwawet and the necropolis guards at Siut will have continued their duties only so long as Hepzefi's mortuary priest received his income and was true to his obligations in reminding them of theirs, and in seeing to it that these obligations were met. We find such an endowment surviving a change of dynasty (from the Fourth to the Fifth), and lasting at least some thirty or forty years, in the middle of the twenty-eighth century before Christ. 3 In the Twelfth Dynasty, too, there was in Upper Egypt great respect for the ancestors of the Old Kingdom. The nomarchs of El-Bersheh, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries before Christ, repaired the tombs of their ancestors of the Pyramid Age, tombs then over six hundred years old, and therefore in a state of ruin. The pious nomarch used to record his restoration in these words: "He (the nomarch) made (it) as his monument for his fathers, who are in the necropolis, the lords of this promontory; restoring what was found in ruin and renewing what was found decayed, the ancestors who were before not having done it." We find the nobles of this province using this formula five times in the tombs of their ancestors. 1 In the same way, Intef, a baron of Hermonthis, says: "I found the chapel of the prince Nekhtyoker fallen to ruin, its walls were old, its statues were shattered, there was no one who cared for them. It was built up anew, its plan was extended, its statues were made anew, its doors were built of stone, that its place might excel beyond that of other august princes." Such piety toward the departed fathers, however, was very rare, and even when shown could not do more than postpone the evil day. The marvel is that with their ancestors’ ruined tombs before them they nevertheless still went on to build for themselves sepulchres which were inevitably to meet the same fate. The tomb of Khnumhotep, the greatest of those left us by the Benihasan lords of four thousand years ago, bears on its walls, among the beautiful paintings which adorn them, the scribblings of a hundred and twenty generations in Egyptian, Coptic, Greek, Arabic, French, Italian, and English. The earliest of these scrawls is that of an Egyptian scribe who entered the tomb-chapel over three thousand years ago and wrote with reed pen and ink upon the wall these words: "The scribe Amenmose came to see the temple of Khufu and found it like the heavens when the sun rises therein." The chapel was some seven hundred years old when this scribe entered it, and its owner, although one of the greatest lords of his time, was so completely forgotten that the visitor, finding the name of Khufu in a casual geographical reference among the inscriptions on the wall, mistook the place for a chapel of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid. All knowledge of the noble and of the endowments which were to support him in the hereafter had disappeared in spite of the precautions which we have read above. How vain and futile now appear the imprecations on these time-stained walls!

But the Egyptian was not wholly without remedy even in the face of this dire contingency. He endeavored to meet the difficulty by engraving on the front of his tomb, prayers believed to be efficacious in supplying all the needs of the dead in the hereafter. All passers-by were solemnly adjured to utter these prayers on behalf of the dead.

The belief in the effectiveness of the uttered word on behalf of the dead had developed enormously since the Old Kingdom. This is a development which accompanies the popularization of the mortuary customs of the upper classes. In the Pyramid Age, as we have seen, such utterances were confined to the later pyramids. These concern exclusively the destiny of the Pharaoh in the hereafter. They were now largely appropriated by the middle and the official class. At the same time there emerge similar utterances, identical in function but evidently more suited to the needs of common mortals. These represent, then, a body of similar mortuary literature among the people of the Feudal Age, some fragments of which are much older than this age. Later the Book of the Dead was made up of selections from this humbler and more popular mortuary literature. Copious extracts from both the Pyramid Texts and these forerunners of the Book of the Dead, about half from each of the two sources, were now written on the inner surfaces of the heavy cedar coffins, in which the better burials of this age are found. The number of such mortuary texts is still constantly increasing as additional coffins from this age are found. Every local coffin-maker was furnished by the priests of his town with copies of these utterances. Before the coffins were put together, the scribes in the maker's employ filled the inner surfaces with pen-and-ink copies of such texts as he had available. It was all done with great carelessness and inaccuracy, the effort being to fill up the planks as fast as possible. They often wrote the same chapter over twice or three times in the same coffin, and in one instance a chapter is found no less than five times in the same coffin.

In so far as these Coffin Texts are identical with the Pyramid Texts we are already familiar with their general function and content. The hereafter to which these citizens of the Feudal Age looked forward was, therefore, still largely celestial and Solar as in the Pyramid Age. But even these early chapters of the Book of the Dead disclose a surprising predominance of the celestial hereafter. There is the same identification with the Sun-god which we found in the Pyramid Texts. There is a chapter of "Becoming Re-Atum," 2 and several of "Becoming a Falcon." The deceased, now no longer the king, as in the Pyramid Texts, says: "I am the soul of the god, self-generator. . . . I have become he. I am he before whom the sky is silent, I am he before whom the earth is ⌈. . . ⌉ . . . I have become the limbs of the god, self-generator. He has made me into his heart (understanding), he has fashioned me into his soul. I am one who has ⌈breathed⌉ the form of him who fashioned me, the august god, self-generator, whose name the gods know not. . . . He has made me into his heart, he has fashioned me into his soul, I was not born with a birth." This identification of the deceased with the Sun-god alternates with old pictures of the Solar destiny, involving only association with the Sun-god. There is a chapter of "Ascending to the Sky to the Place where Re is," another of "Embarking in the Ship of Re when he has Gone to his Ka; and a "Chapter of Entering Into the West among the Followers of Re Every Day." When once there the dead man finds among his resources a chapter of "Being the Scribe of Re." He also has a chapter of "Becoming One Revered by the King," presumably meaning the Sun-god, as the chapter is a magical formulary for accomplishing the ascent to the sky. In the same way he may become an associate of the Sun-god by using a chapter of "Becoming One of ⌈the Great⌉ of Heliopolis."

The famous seventeenth chapter of the Book of the Dead was already a favorite chapter in this age, and begins the texts on a number of coffins. It is largely an identification of the deceased with the Sun-god, although other gods also appear. The dead man says:

"I am Atum, I who was alone;

I am Re at his first appearance.

I am the Great God, self-generator,

Who fashioned his names, lord of gods,

Whom none approaches among the gods.

I was yesterday, I know to-morrow.

The battle-field of the gods was made when I spake.

I know the name of that Great God who is therein.

'Praise-of-Re' is his name.

I am that great Phœnix which is in Heliopolis."

Just as in the Pyramid Texts, however, so in these early Texts of the Book of the Dead, the Osirian theology has intruded and has indeed taken possession of them. Already in the Feudal Age this ancient Solar text had been supplied with an explanatory commentary, which adds to the line, "I was yesterday, I know to-morrow," the words, "that is Osiris." The result of this Osirianization was the intrusion of the Osirian subterranean hereafter, even in Solar and celestial texts. Thus this seventeenth chapter was supplied with a title reading, "Chapter of Ascending by Day from the Nether World." This title is not original, and is part of the Osirian editing, which involuntarily places the sojourn of the dead in the Nether World though it cannot eliminate all the old Solar texts. The titles now commonly appended to these texts frequently conclude with the words, "in the Nether World." We find a chapter for "The Advancement of a Man in the Nether World," although it is devoted throughout to Solar and celestial conceptions. In the Pyramid Texts, as we have seen, the intrusion of Osiris did not result in altering the essentially celestial character of the hereafter to which they are devoted. In the Coffin Texts we have not only the commingling of Solar and Osirian beliefs which now more completely coalesce than before, but the result is that Re is intruded into the subterranean hereafter. The course of events may be stated in somewhat exaggerated form if we say that in the Pyramid Texts Osiris was lifted skyward, while in the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead, Re is dragged earthward.

The resulting confusion is even worse than in the Pyramid Texts. We shall shortly find Re appearing with subterranean functions on behalf of the dead, functions entirely unknown in the Pyramid Texts. The old Solar idea that the dead might become the scribe of Re, we have already found in the Coffin Texts; but while the title is given as "Being the Scribe of Re," the text begins, "I am Kerkeru, scribe of Osiris." 1 We can hardly conceive a mass of mortuary doctrine containing a "Chapter of Reaching Orion," a fragment of ancient celestial belief, side by side with such chapters as "Burial in the West," "That the Beautiful West Rejoice at the Approach of a Man," "Chapter of Becoming the Nile," 5 which is, of course, a purely Osirian title although the text of the chapter is Solar; or a chapter of "Becoming the Harvest-god (Neper)," in which the deceased is identified with Osiris and with barley, as well as with Neper, god of harvest and grain.

The Coffin Texts already display the tendency, carried so much further by the Book of the Dead, of enabling the deceased to transform himself at will into various beings. It was this notion which led Herodotus to conclude that the Egyptians believed in what we now call transmigration of souls, but this is a mistaken impression on his part. Besides identification with Re, Osiris, and other gods, which, of course, involved belief in a transformation, the Coffin Texts also enable the deceased to "become the blazing Eye of Horus." By the aid of another chapter he can accomplish the "transformation into an ekhet-bird" or "into the servant at the table of Hathor."

It is difficult to gain any coherent conception of the hereafter which the men of this age thus hoped to attain. There are the composite Solar-Osirian pictures which we have already found in the Pyramid Texts, and in which the priests to whom we owe these Coffin Text compilations allow their fancy to roam at will. The deceased citizen, now sharing the destiny of Osiris and called such by Horus, hears himself receiving words of homage and promises of felicity addressed to him by his divine son:

"I come, I am Horus who opens thy mouth, together with Ptah who glorifies thee, together with Thoth who gives to thee thy heart (understanding); . . . that thou mayest remember what thou hadst forgotten. I cause that thou eat bread at the desire of thy body. I cause that thou remember what thou hast forgotten. I cause that thou eat bread . . . more than thou didst on earth. I give to thee thy two feet that thou mayest make the going and coming of thy two soles (or sandals). I cause that thou shouldst carry out commissions with the south wind and shouldst run with the north wind. . . . I cause that thou shouldst ferry over ⌈Peterui⌉ and ferry over the lake of thy wandering and the sea of (thy) sandal as thou didst on earth. Thou rulest the streams and the Phœnix. . . . Thou leviest on the royal domains. Thou repulsest the violent who comes in the night, the robber of early morning. . . . Thou goest around the countries with Re; he lets thee see the pleasant places, thou findest the valleys filled with water for washing thee and for cooling thee, thou pluckest marsh-flowers and heni-blossoms, lilies and lotus-flowers. The bird-pools come to thee by thousands, lying in thy path; when thou hast hurled thy boomerang against them, it is a thousand that fall at the sound of the wind thereof. They are ro-geese, green-fronts, quails, and kunuset. I cause that there be brought to thee the young gazelles, ⌈bullocks⌉ of white bulls; I cause that there be brought to thee males of goats and grain-fed males of sheep. There is fastened for thee a ladder to the sky. Nut gives to thee her two arms. Thou sailest in the Lily-lake. Thou bearest the wind in an eight-ship. These two fathers (Re and Atum) of the Imperishable Stars and of the Unweariable Stars sail thee. They command thee, they tow thee through the district with their imperishable ropes."

In another Solar-Osirian chapter, after the deceased is crowned, purified, and glorified, he enters upon the Solar voyage as in the Pyramid Texts. It is then said of him: "Brought to thee are blocks of silver and ⌈masses⌉ of malachite. Hathor, mistress of Byblos, she makes the rudders of thy ship. . . . It is said to thee, 'Come into the broad-hall,' by the Great who are in the temple. Bared to thee are the Four Pillars of the Sky, thou seest the secrets that are therein, thou stretchest out thy two legs upon the Pillars of the Sky and the wind is sweet to thy nose."

While the destiny, everywhere so evidently royal in the Pyramid Texts, has thus become the portion of any one, the simpler life of the humbler citizen which he longed to see continued in the hereafter is quite discernible, also in these Coffin Texts. As he lay in his coffin he could read a chapter which concerned "Building a house for a man in the Nether World, digging a pool and planting fruit-trees." Once supplied with a house, surrounded by a garden with its pool and its shade-trees, the dead man must be assured that he shall be able to occupy it, and hence a "chapter of a man's being in his house." The lonely sojourn there without the companionship of family and friends was an intolerable thought, and hence a further chapter entitled "Sealing of a Decree concerning the Household, to give the Household [to a man] in the Nether World." In the text the details of the decree are five times specified in different forms. "Geb, hereditary prince of the gods, has decreed that there be given to me my household, my children, my brothers, my father, my mother, my slaves, and all my establishment." Lest they should be withheld by any malign influence the second paragraph asserts that "Geb, hereditary prince of the gods, has said to release for me my household, ⌈my⌉ children, my brothers and sisters, my father, my mother, all my slaves, all my establishment at once, rescued from every god, from every goddess, from every death (or dead person)." To assure the fulfilment of this decree there was another chapter entitled "Uniting of the Household of a Man with Him in the Nether World," which effected the "union of the household, father, mother, children, friends, ⌈connections⌉, wives, concubines, slaves, servants, everything belonging to a man, with him in the Nether World."

The rehabilitation of a man's home and household in the hereafter was a thought involving, more inevitably even than formerly, the old-time belief in the necessity of food. It reminds us of the Pyramid Texts when we find a chapter of "Causing that X Raise Himself Upon his Right Side." The mummy lies upon the left side, and he rises to the other side in order that he may partake of food. Hence, another "Chapter of Eating Bread in the Nether World," or "Eating of Bread on the Table of Re, Giving of Plenty in Heliopolis." 4 The very next chapter shows us how "the sitter sits to eat bread when Re sits to eat bread. . . . Give to me bread when I am hungry. Give to me beer when I am thirsty."

A tendency which later came fully to its own in the Book of the Dead is already the dominant tendency in these Coffin Texts. It regards the hereafter as a place of innumerable dangers and ordeals, most of them of a physical nature, although they sometimes concern also the intellectual equipment of the deceased. The weapon to be employed and the surest means of defence available to the deceased was some magical agency, usually a charm to be pronounced at the critical moment. This tendency then inclined to make the Coffin Texts, and ultimately the Book of the Dead which grew out of them, more and more a collection of charms, which were regarded as inevitably effective in protecting the dead or securing for him any of the blessings which were desired in the life beyond the grave. There was, therefore, a chapter of "Becoming a Magician," addressed to the august ones who are in the presence of Atum the Sun-god. It is, of course, itself a charm and concludes with the words, "I am a magician." 1 Lest the dead man should lose his magic power, there was a ceremony involving the "attachment of a charm so that the magical power of man may not be taken away from him in the Nether World." 2 The simplest of the dangers against which these charms were supplied doubtless arose in the childish imagination of the common folk. They are frequently grotesque in the extreme. We find a chapter "preventing that the head of a man be taken from him." 3 There is the old charm found also in the Pyramid Texts to prevent a man from being obliged to eat his own foulness. 4 He is not safe from the decay of death; hence there are two chapters that "a man may not decay in the Nether World." 5 But the imagination of the priests, who could only gain by the issuance of ever new chapters, undoubtedly contributed much to heighten the popular dread of the dangers of the hereafter and spread the belief in the usefulness of such means for meeting them. We should doubtless recognize the work of the priests in the figure of a mysterious scribe named Gebga, who is hostile to the dead, so that a charm was specially devised to enable the dead man to break the pens, smash the writing outfit, and tear up the rolls of the malicious Gebga. 6 That menacing danger which was also feared in the Pyramid Texts, the assaults of venomous serpents, must likewise be met by the people of the Feudal Age. The dead man, therefore, finds in his roll charms for "Repulsing Apophis from the Barque of Re" and for "Repulsing the Serpent which ⌈Afflicts⌉ the Kas," 1 not to mention also one for "Repulsing Serpents and Repulsing Crocodiles." The way of the departed was furthermore beset with fire, and he would be lost without a charm for "Going Forth from the Fire," or of "Going Forth from the Fire Behind the Great God." 4 When he was actually obliged to enter the fire he might do so with safety by means of a "Chapter of Entering Into the Fire and of Coming Forth from the Fire Behind the Sky." Indeed, the priests had devised a chart of the journey awaiting the dead, guiding him through the gate of fire at the entrance and showing the two ways by which he might proceed, one by land and the other by water, with a lake of fire between them. This Book of the Two Ways, with its map of the journey, was likewise recorded in the coffin. 6 In spite of such guidance it might unluckily happen that the dead wander into the place of execution of the gods; but from this he was saved by a chapter of "Not Entering Into the Place of Execution of the Gods; 7 and lest he should suddenly find himself condemned to walk head downward, he was supplied with a "Chapter of Not Walking Head Downward." 1 These unhappy dead who were compelled to go head downward were the most malicious enemies in the hereafter. Protection against them was vitally necessary. It is said to the deceased: "Life comes to thee, but death comes not to thee. . . . They (Orion, Sothis, and the Morning Star) save thee from the wrath of the dead who go head downward. Thou art not among them. . . . Rise up for life, thou diest not; lift thee up for life, thou diest not." The malice of the dead was a danger constantly threatening the newly arrived soul, who says: "He causes that I gain the power over my enemies. I have expelled them from their tombs. I have overthrown them in their (tomb-) chapels. I have expelled those who were in their places. I have opened their mummies, destroyed their kas. I have suppressed their souls. . . . An edict of the Self-Generator has been issued against my enemies among the dead, among the living, dwelling in sky and earth." The belief in the efficacy of magic as an infallible agent in the hand of the dead man was thus steadily growing, and we shall see it ultimately dominating the whole body of mortuary belief as it emerges a few centuries later in the Book of the Dead. It cannot be doubted that the popularity of the Osirian faith had much to do with this increase in the use of mortuary magical agencies. The Osiris myth, now universally current, made all classes familiar with the same agencies employed by Isis in the raising of Osiris from the dead, while the same myth in its various versions told the people how similar magical power had been employed by Anubis, Thoth, and Horus on behalf of the dead and persecuted Osiris.

p. 285

Powerful as the Osiris faith had been in the Pyramid Age, its wide popularity now surpassed anything before known. We see in it the triumph of folk-religion as opposed to or contrasted with a state cult like that of Re. The supremacy of Re was a political triumph; that of Osiris, while unquestionably fostered by an able priesthood probably practising constant propaganda, was a triumph of popular faith among all classes of society, a triumph which not even the court and the nobles were able to resist. The blessings which the Osirian destiny in the hereafter offered to all proved an attraction of universal power. If they had once been an exclusively royal prerogative, as was the Solar destiny in the Pyramid Texts, we have seen that even the royal Solar hereafter had now been appropriated by all. One of the ancient tombs of the Thinite kings at Abydos, a tomb now thirteen or fourteen hundred years old, had by this time come to be regarded as the tomb of Osiris. It rapidly became the Holy Sepulchre of Egypt, to which all classes pilgrimaged. The greatest of all blessings was to be buried in the vicinity of this sacred tomb, and more than one functionary took advantage of some official journey or errand to erect a tomb there. 1 If a real tomb was impossible, it was nevertheless beneficial to build at least a false tomb there bearing one's name and the names of one's family and relatives. Failing this, great numbers of pilgrims and visiting officials each erected a memorial tablet or stela bearing prayers to the great god on behalf of the visitor and his family. Thus an official of Amenemhet II, who was sent by the king on a journey of inspection among the temples of the South, says on his stela found at Abydos: "I fixed my name at the place where is the god Osiris, First of the Westerners, Lord of Eternity, Ruler of the West, (the place) to which all that is flees, for the sake of the benefit therein, in the midst of the followers of the Lord of Life, that I might eat his loaf and 'ascend by day'; that my soul might enjoy the ceremonies of people kind in heart toward my tomb and in hand toward my stela." Another under Sesostris I says: "I have made this tomb at the stairway of the Great God, in order that I may be among his followers, while the soldiers who follow his majesty give to my ka of his bread and his ⌈provision⌉, just as every royal messenger does who comes inspecting the boundaries of his majesty." The enclosure and the approach to the temple of Osiris were filled with these memorials, which as they survive to-day form an important part of our documentary material for the history of this age. The body of a powerful baron might even be brought to Abydos to undergo certain ceremonies there, and to bring back certain things to his tomb at home, as the Arab brings back water from the well of Zemzem, or as Roman ladies brought back sacred water from the sanctuary of Isis at Philæ. Khnumhotep of Benihasan has depicted on the walls of his tomb-chapel this voyage on the Nile, showing his embalmed body resting on a funeral barge which is being towed northward, accompanied by priests and lectors. The inscription calls it the "voyage up-stream to know the things of Abydos." A pendent scene showing a voyage down-stream is accompanied by the words, "the return bringing the things of Abydos." Just what these sacred "things of Abydos" may have been we have no means of knowing, 1 but it is evident that on this visit to the great god at Abydos, it was expected that the dead might personally present himself and thus ensure himself the favor of the god in the hereafter.

The visitors who thus came to Abydos, before or after death, brought so many votive offerings that the modern excavators of the Osiris tomb found it deeply buried under a vast accumulation of broken pots and other gifts left there by the pilgrims of thousands of years. There must eventually have been multitudes of such pilgrims at this Holy Sepulchre of Egypt at all times, but especially at that season when in the earliest known drama the incidents of the god's myth were dramatically re-enacted in what may properly be called a "passion play." Although this play is now completely lost, the memorial stone of Ikhernofret, an officer of Sesostris III, who was sent by the king to undertake some restorations in the Osiris temple at Abydos, a stone now preserved in Berlin, furnishes an outline from which we may draw at least the titles of the most important acts. These show us that the drama must have continued for a number of days, and that each of the more important acts probably lasted at least a day, the multitude participating in much that was done. In the brief narrative of Ikhernofret we discern eight acts.

The first discloses the old mortuary god Upwawet issuing in procession that he may scatter the enemies of Osiris and open the way for him. In the second act Osiris himself appears in his sacred barque, into which ascend certain of the pilgrims. Among these is Ikhernofret, as he proudly tells in his inscription. There he aids in repelling the foes of Osiris who beset the course of the barque, and there is undoubtedly a general melée of the multitude, such as Herodotus saw at Papremis fifteen hundred years later, some in the barque defending the god, and others, proud to carry away a broken head on behalf of the celebration, acting as his enemies in the crowd below. Ikhernofret, like Herodotus, passes over the death of the god in silence. It was a thing too sacred to be described. He only tells that he arranged the "Great Procession" of the god, a triumphal celebration of some sort, when the god met his death. This was the third act. In the fourth Thoth goes forth and doubtless finds the body, though this is not stated. The fifth act is made up of the sacred ceremonies by which the body of the god is prepared for entombment, while in the sixth we behold the multitude moving out in a vast throng to the Holy Sepulchre in the desert behind Abydos to lay away the body of the dead god in his tomb. The seventh act must have been an imposing spectacle. On the shore or water of Nedyt, near Abydos, the enemies of Osiris, including of course Set and his companions, are overthrown in a great battle by Horus, the son of Osiris. The raising of the god from the dead is not mentioned by Ikhernofret, but in the eighth and final act we behold Osiris, restored to life, entering the Abydos temple in triumphal procession. It is thus evident that the drama presented the chief incidents in the myth.

As narrated by Ikhernofret, the acts in which he participated were these:

(1) "I celebrated the 'Procession of Upwawet' when he proceeded to champion his father (Osiris)."

(2) "I repulsed those who were hostile to the Neshmet barque, and I overthrew the enemies of Osiris."

(3) "I celebrated the 'Great Procession,' following the god in his footsteps."

(4) "I sailed the divine barque, while Thoth . . . the voyage."

(5) "I equipped the barque (called) 'Shining in Truth,' of the Lord of Abydos, with a chapel; I put on his beautiful regalia when he went forth to the district of Peker."

(6) "I led the way of the god to his tomb in Peker."

(7) "I championed Wennofer (Osiris) on 'That Day of the Great Battle'; I overthrew all the enemies upon the shore of Nedyt."

(8) "I caused him to proceed into the barque (called) 'The Great'; it bore his beauty; I gladdened the heart of the eastern highlands; I [put] jubilation in the western highlands, when they saw the beauty of the Neshmet barque. It landed at Abydos and they brought [Osiris, First of the Westerners, Lord] of Abydos to his palace."

It is evident that such popular festivals as these gained a great place in the affections of the people, and over and over again, on their Abydos tablets, the pilgrims pray that after death they may be privileged to participate in these celebrations, just as Hepzefi arranged to do so in those at Siut. Thus presented in dramatic form the incidents of the Osiris myth made a powerful impression upon the people. The "passion play" in one form or another caught the imagination of more than one community, and just as Herodotus found it at Papremis, so now it spread from town to town, to take the chief place in the calendar of festivals. Osiris thus gained a place in the life and the hopes of the common people held by no other god. The royal destiny of Osiris and his triumph over death, thus vividly portrayed in dramatic form, rapidly disseminated among the people the belief that this destiny, once probably reserved for the king, might be shared by all. As we have said before, it needed but the same magical agencies employed by Isis to raise her dead consort, or by Horus, Anubis, and Thoth, as they wrought on behalf of the slain Osiris, to bring to every man the blessed destiny of the departed god. Such a development of popular mortuary belief, as we have already seen, inevitably involved also a constantly growing confidence in the efficiency of magic in the hereafter.

It is difficult for the modern mind to understand how completely the belief in magic penetrated the whole substance of life, dominating popular custom and constantly appearing in the simplest acts of the daily household routine, as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food. It constituted the very atmosphere in which the men of the early Oriental world lived. Without the saving and salutary influence of such magical agencies constantly invoked, the life of an ancient household in the East was unthinkable. The destructive powers would otherwise have annihilated all. While it was especially against disease that such means must be employed, the ordinary processes of domestic and economic life were constantly placed under its protection. The mother never hushed her ailing babe and laid it to rest without invoking unseen powers to free the child from the dark forms of evil, malice, and disease that lurked in every shadowy corner, or, slinking in through the open door as the gloom of night settled over the house, entered the tiny form and racked it with fever. Such demons might even assume friendly guise and approach under pretext of soothing and healing the little sufferer. We can still hear the mother's voice as she leans over her babe and casts furtive glances through the open door into the darkness where the powers of evil dwell.

"Run out, thou who comest in darkness, who enterest in ⌈stealth⌉, his nose behind him, his face turned backward, who loses that for which he came."

"Run out, thou who comest in darkness, who enterest in ⌈stealth⌉, her nose behind her, her face turned backward, who loses that for which she came."

"Comest thou to kiss this child? I will not let thee kiss him."

"Comest thou to soothe (him)? I will not let thee soothe him.

"Comest thou to harm him? I will not let thee harm him.

"Comest thou to take him away? I will not let thee take him away from me.

"I have made his protection against thee out of Efet-herb, it makes pain; out of onions, which harm thee; out of honey which is sweet to (living) men and bitter to those who are yonder (the dead); out of the evil (parts) of the Ebdu-fish; out of the jaw of the meret; out of the backbone of the perch."

The apprehensive mother employs not only the uttered charm as an exorcism, but adds a delectable mixture of herbs, honey, and fish to be swallowed by the child, and designed to drive out the malignant demons, male and female, which afflict the baby with disease or threaten to carry it away. A hint as to the character of these demons is contained in the description of honey as "sweet to men (meaning the living) and bitter to those who are yonder (the dead)." It is evident that the demons dreaded were some of them the disembodied dead. At this point the life of the living throughout its course impinged upon that of the dead. The malicious dead must be bridled and held in check. Charms and magical devices which had proved efficacious against them during earthly life might prove equally valuable in the hereafter. This charm which prevented the carrying away of the child might also be employed to prevent a man's heart from being taken away in the Nether World. The dead man need only say: "Hast thou come to take away this my living heart? This my living heart is not given to thee;" whereupon the demon that would seize and flee with it must inevitably slink away.

Thus the magic of daily life was more and more brought to bear on the hereafter and placed at the service of the dead. As the Empire rose in the sixteenth century B.C., we find this folk-charm among the mortuary texts inserted in the tomb. It is embodied in a charm now entitled "Chapter of Not Permitting a Man's Heart to be Taken Away from Him in the Nether World," a chapter which we found already in the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom. These charms have now increased in number, and each has its title indicating just what it is intended to accomplish for the deceased. Combined with some of the old hymns of praise to Re and Osiris, some of which might be recited at the funeral, 1 and usually including also some account of the judgment, these mortuary texts were now written on a roll of papyrus and deposited with the dead in the tomb. It is these papyri which have now commonly come to be called the Book of the Dead. As a matter of fact, there was in the Empire no such book. 2 Each roll contained a random collection of such mortuary texts as the scribal copyist happened to have at hand, or those which he found enabled him best to sell his rolls; that is, such as enjoyed the greatest popularity. There were sumptuous and splendid rolls, sixty to eighty feet long and containing from seventy-five to as many as a hundred and twenty-five or thirty chapters. On the other hand, the scribes also copied small and modest rolls but a few feet in length, bearing but a meagre selection of the more important chapters. No two rolls exhibit the same collection of charms and chapters throughout, and it was not until the Ptolemaic period, some time after the fourth century B.C., that a more nearly canonical selection of chapters was gradually introduced. It will be seen, then, as we have said, that, properly speaking, there was in the Empire no Book of the Dead, but only various groups of mortuary chapters filling the mortuary papyri of the time. The entire body of chapters from which these rolls were made up, were some two hundred in number, although even the largest rolls did not contain them all. The independence or identity of each chapter is now evident in the custom of prefixing to every chapter a title—a custom which had begun in the case of many chapters in the Coffin Texts. Groups of chapters forming the most common nucleus of the Book of the Dead were frequently called "Chapters of Ascending by Day," a designation also in use in the Coffin Texts (see p. 276); but there was no current title for a roll of the Book of the Dead as a whole.

While a few scanty fragments of the Pyramid Texts have survived in the Book of the Dead, it may nevertheless be said that they have almost disappeared. 1 The Coffin Texts reappear, however, in increasing numbers and contribute largely to the various collections which make up the Book of the Dead. An innovation of which only indications are found in the Coffin Texts is the insertion in the Empire rolls of gorgeous vignettes illustrating the career of the deceased in the next world. Great confidence was placed in their efficacy, especially, as we shall see, in the scene of the judgment, which was now elaborately illustrated. It may be said that these illustrations in the Book of the Dead are another example of the elaboration of magical devices designed to ameliorate the life beyond the grave. Indeed, the Book of the Dead itself, as a whole, is but a far-reaching and complex illustration of the increasing dependence on magic in the hereafter.

The benefits to be obtained in this way were unlimited, and it is evident that the ingenuity of a mercenary priesthood now played a large part in the development which followed. To the luxurious nobles of the Empire, the old peasant vision of the hereafter where the dead man might plough and sow and reap in the happy fields, and where the grain grew to be seven cubits (about twelve feet) high, 1 did not appear an attractive prospect. To be levied for labor and to be obliged to go forth and toil, even in the fields of the blessed, no longer appealed to the pampered grandees of an age of wealth and luxury. Already in the Middle Kingdom wooden figures of the servants of the dead were placed in the tomb, that they might labor for him in death as they had done in life. This idea was now carried somewhat further. Statuettes of the dead man bearing sack and hoe were fashioned, and a cunning charm was devised and written upon the breast of the figure: "O statuette, counted for X (name of deceased), if I am called, if I am counted to do any work that is done in the Nether World, . . . thou shalt count thyself for me at all times, to cultivate the fields, to water the shores, to transport sand of the east to the west, and say, 'Here am I." This charm was placed among those in the roll, with the title, "Chapter of Causing that the Statuette Do the Work of a Man in the Nether World." The device was further elaborated by finally placing one such little figure of the dead in the tomb for each day in the year, and they have been found in the Egyptian cemeteries in such numbers that museums and private collections all over the world, as has been well said, are "populated" with them.

With such means of gain so easily available, we cannot wonder that the priests and scribes of this age took advantage of the opportunity. The dangers of the hereafter were now greatly multiplied, and for every critical situation the priest was able to furnish the dead with an effective charm which would infallibly save him. Besides many charms which enabled the dead to reach the world of the hereafter, there were those which prevented him from losing his mouth, his head, his heart, others which enabled him to remember his name, to breathe, eat, drink, avoid eating his own foulness, to prevent his drinking-water from turning into flame, to turn darkness into light, to ward off all serpents and other hostile monsters, and many others. The desirable transformations, too, had now increased, and a short chapter might in each case enable the dead man to assume the form of a falcon of gold, a divine falcon, a lily, a Phœnix, a heron, a swallow, a serpent called "son of earth," a crocodile, a god, and, best of all, there was a chapter so potent that by its use a man might assume any form that he desired.

It is such productions as these which form by far the larger proportion of the mass of texts which we term the Book of the Dead. To call it the Bible of the Egyptians, then, is quite to mistake the function and content of these rolls. 1 The tendency which brought forth this mass of "chapters" is also characteristically evident in two other books each of which was in itself a coherent and connected composition. The Book of the Two Ways, as old, we remember, as the Middle Kingdom, 1 had already contributed much to the Book of the Dead regarding the fiery gates through which the dead gained entrance to the world beyond and to the two ways by which he was to make his journey. On the basis of such fancies as these, the imagination of the priests now put forth a "Book of Him Who is in the Nether World," describing the subterranean journey of the sun during the night as he passed through twelve long cavernous galleries beneath the earth, each one representing a journey of an hour, the twelve caverns leading the sun at last to the point in the east where he rises. The other book, commonly called the "Book of the Gates, "represents each of the twelve caverns as entered by a gate and concerns itself with the passage of these gates. While these compositions never gained the popularity enjoyed by the Book of the Dead, they are magical guide-books devised for gain, just as was much of the material which made up the Book of the Dead.

That which saves the Book of the Dead itself from being exclusively a magical vade mecum for use in the hereafter is its elaboration of the ancient idea of the moral judgment, and its evident appreciation of the burden of conscience. The relation with God had become something more than merely the faithful observance of external rites. It had become to some extent a matter of the heart and of character. Already in the Middle Kingdom the wise man had discerned the responsibility of the inner man, of the heart or understanding. The man of ripe and morally sane understanding is his ideal, and his counsel is to be followed. "A hearkener (to good counsel) is one whom the god loves. Who hearkens not is one whom the god hates. It is the heart (understanding) which makes its possessor a hearkener or one not hearkening. The life, prosperity, and health of a man is in his heart." 1 A court herald of Thutmose III in recounting his services likewise says: "It was my heart which caused that I should do them (his services for the king), by its guidance of my affairs. It was . . . as an excellent witness. I did not disregard its speech, I feared to transgress its guidance. I prospered thereby greatly, I was successful by reason of that which it caused me to do, I was distinguished by its guidance. 'Lo, . . . ,' said the people, 'it is an oracle of God in every body. 2 Prosperous is he whom it has guided to the good way of achievement, 'Lo, thus I was." The relatives of Paheri, a prince of El Kab, addressing him after his death, pray, "Mayest thou spend eternity in gladness of heart, in the favor of the god that is in thee," 4 and another dead man similarly declares, "The heart of a man is his own god, and my heart was satisfied with my deeds." To this inner voice of the heart, which with surprising insight was even termed a man's god, the Egyptian was now more sensitive than ever before during the long course of the ethical evolution which we have been following. This sensitiveness finds very full expression in the most important if not the longest section of the Book of the Dead. Whereas the judgment hereafter is mentioned as far back as the Pyramid Age, we now find a full account and description of it in the Book of the Dead. 1 Notwithstanding the prominence of the intruding Osiris in the judgment we shall clearly discern its Solar origin and character even as recounted in the Book of the Dead. Three different versions of the judgment, doubtless originally independent, have been combined in the fullest and best rolls. The first is entitled, "Chapter of Entering Into the Hall of Truth (or Righteousness)," and it contains "that which is said on reaching the Hall of Truth, when X (the deceased's name) is purged from all evil that he has done, and he beholds the face of the god. 'Hail to thee, great god, lord of Truth. 3 I have come to thee, my lord, and I am led (thither) in order to see thy beauty. I know thy name, I know the names of the forty-two gods who are with thee in the Hall of Truth, who live on evil-doers and devour their blood, on that day of reckoning character before Wennofer (Osiris). Behold, I come to thee, I bring to thee righteousness and I expel for thee sin. I have committed no sin against people. . . . I have not done evil in the place of truth. I knew no wrong. I did no evil thing. . . . I did not do that which the god abominates.

I did not report evil of a servant to his master. I allowed no one to hunger. I caused no one to weep. I did not murder. I did not command to murder. I caused no man misery. I did not diminish food in the temples. I did not decrease the offerings of the gods. I did not take away the food-offerings of the dead (literally "glorious"). I did not commit adultery. I did not commit self-pollution in the pure precinct of my city-god. I did not diminish the grain measure. I did not diminish the span. I did not diminish the land measure. I did not load the weight of the balances. I did not deflect the index of the scales. I did not take milk from the mouth of the child. I did not drive away the cattle from their pasturage. I did not snare the fowl of the gods. I did not catch the fish in their pools. I did not hold back the water in its time. I did not dam the running water. I did not quench the fire in its time. I did not withhold the herds of the temple endowments. I did not interfere with the god in his payments. I am purified four times, I am pure as that great Phœnix is pure which is in Heracleopolis. For I am that nose of the Lord of Breath who keeps alive all the people.'" The address of the deceased now merges into obscure mythological allusions, and he concludes with the statement, "There arises no evil thing against me in this land, in the Hall of Truth, because I know the names of these gods who are therein, the followers of the Great God."

A second scene of judgment is now enacted. The judge Osiris is assisted by forty-two gods who sit with him in judgment on the dead. They are terrifying demons, each bearing a grotesque and horrible name, which the deceased claims that he knows. He therefore addresses them one after the other by name. They are such names as these: "Broad-Stride-that-Came-out-of-Heliopolis," "Flame-Hugger-that-Came-out-of-Troja," "Nosey-that-Came-out-of-Hermopolis," "Shadow-Eater-that-Came-out-of-the-Cave," "Turn-Face-that-Came-out-of-Rosta," "Two-Eyes-of-Flame-that-Came-out-of-Letopolis," "Bone-Breaker-that-Came-out-of-Heracleopolis," "White-Teeth-that-Came-out-of -the-Secret-Land," "Blood-Eater-that-Came-out-of-the-Place-of-Execution," "Eater-of-Entrails-that-Came-out-of-Mebit." These and other equally edifying creations of priestly imagination the deceased calls upon, addressing to each in turn a declaration of innocence of some particular sin.

This section of the Book of the Dead is commonly called the "Confession." It would be difficult to devise a term more opposed to the real character of the dead man's statement, which as a declaration of innocence is, of course, the reverse of a confession. The ineptitude of the designation has become so evident that some editors have added the word negative, and thus call it the "negative confession," which means nothing at all. The Egyptian does not confess at this judgment, and this is a fact of the utmost importance in his religious development, as we shall see. To mistake this section of the Book of the Dead for "confession" is totally to misunderstand the development which was now slowly carrying him toward that complete acknowledgment and humble disclosure of his sin which is nowhere found in the Book of the Dead.

It is evident that the forty-two gods are an artificial creation. As was long ago noticed, they represent the forty or more nomes, or administrative districts, of Egypt. The priests doubtless built up this court of forty-two judges in order to control the character of the dead from all quarters of the country. The deceased would find himself confronted by one judge at least who was acquainted with his local reputation, and who could not be deceived. The forty-two declarations addressed to this court cover much the same ground as those we have already rendered in the first address. The editors had some difficulty in finding enough sins to make up a list of forty-two, and there are several verbal repetitions, not to mention essential repetitions with slight changes in the wording. The crimes which may be called those of violence are these: "I did not slay men (5), I did not rob (2), I did not steal (4), I did not rob one crying for his possessions (18), 1 my fortune was not great but by my (own) property (41), I did not take away food (10), I did not stir up fear (21), I did not stir up strife (25)." Deceitfulness and other undesirable qualities of character are also disavowed:

"I did not speak lies (9), I did not make falsehood in the place of truth (40), I was not deaf to truthful words (24), I did not diminish the grain-measure (6), I was not avaricious (3), my heart devoured not (coveted not?) (28), my heart was not hasty (31), I did not multiply words in speaking (33), my voice was not over loud (37), my mouth did not wag (lit. go) (17), I did not wax hot (in temper) (23), I did not revile (29), I was not an eavesdropper (16), I was not puffed up (39)." The dead man is free from sexual immorality: "I did not commit adultery with a woman (19), I did not commit self-pollution (20, 27);" and ceremonial transgressions are also denied: "I did not revile the king (35), I did not blaspheme the god (38), I did not slay the divine bull (13), I did not steal temple endowment (8), I did not diminish food in the temple (15), I did not do an abomination of the gods (42)." These, with several repetitions and some that are unintelligible, make up the declaration of innocence.

Having thus vindicated himself before the entire great court, the deceased confidently addresses them: "Hail to you, ye gods! I know you, I know your names. I fall not before your blades. Report not evil of me to this god whom ye follow. My case does not come before you. Speak ye the truth concerning me before the All-Lord; because I did the truth (or righteousness) in the land of Egypt. I did not revile the god. My case did not come before the king then reigning. Hail to you, ye gods who are in the Hall of Truth, in whose bodies are neither sin nor falsehood, who live on truth in Heliopolis . . . before Horus dwelling in his sun-disk. 2 Save ye me from Babi, 3 who lives on the entrails of the great, on that day of the great reckoning. Behold, I come to you without sin, without evil, without wrong. . . . I live on righteousness, I feed on the righteousness of my heart. I have done that which men say, and that wherewith the gods are content. I. have satisfied the god with that which he desires. I gave bread to the hungry, water to the thirsty, clothing to the naked, and a ferry to him who was without a boat. I made divine offerings for the gods and food-offerings for the dead. Save ye me; protect ye me. Enter no complaint against me before the Great God. For I am one of pure mouth and pure hands, to whom was said 'Welcome, welcome' by those who saw him." With these words the claims of the deceased to moral worthiness merge into affirmations that he has observed all ceremonial requirements of the Osirian faith, and these form more than half of this concluding address to the gods of the court.

The third record of the judgment was doubtless the version which made the deepest impression upon the Egyptian. Like the drama of Osiris at Abydos, it is graphic and depicts the judgment as effected by the balances. In the sumptuously illustrated papyrus of Ani 2 we see Osiris sitting enthroned at one end of the judgment hall, with Isis and Nephthys standing behind him. Along one side of the hall are ranged the nine gods of the Heliopolitan Ennead, headed by the Sun-god. 3 They afterward announce the verdict, showing the originally Solar origin of this third scene of judgment, in which Osiris has now assumed the chief place. In the midst stand "the balances of Re wherewith he weighs truth," as we have seen them called in the Feudal Age; 4 but the judgment in which they figure has now become Osirianized. The balances are manipulated by the ancient mortuary god Anubis, behind whom stands the divine scribe Thoth, who presides over the weighing, pen and writing palette in hand, that he may record the result. Behind him crouches a grotesque monster called the "Devouress," with the head of a crocodile, fore quarters of a lion and hind quarters of a hippopotamus, waiting to devour the unjust soul. Beside the balances in subtle suggestiveness stands the figure of "Destiny" accompanied by Renenet and Meskhenet, the two goddesses of birth, about to contemplate the fate of the soul at whose coming into this world they had once presided. Behind the enthroned divinities sit the gods "Taste" and "Intelligence." In other rolls we not infrequently find standing at the entrance the goddess "Truth, daughter of Re," who ushers into the hall of judgment the newly arrived soul. Ani and his wife, with bowed heads and deprecatory gestures, enter the fateful hall, and Anubis at once calls for the heart of Ani. In the form of a tiny vase, which is in Egyptian writing the hieroglyph for heart, one side of the balances bears the heart of Ani, while in the other side appears a feather, the symbol and hieroglyph for Truth or Righteousness. At the critical moment Ani addresses his own heart: "O my heart that came from my mother! O my heart belonging to my being! Rise not up against me as a witness. Oppose me not in the council (court of justice). Be not hostile to me before the master of the balances. Thou art my ka that is in my body. . . . Let not my name be of evil odor with the court, speak no lie against me in the presence of the god."

Evidently this appeal has proven effective, for Thoth, "envoy of the Great Ennead, that is in the presence of Osiris," at once says: "Hear ye this word in truth. I have judged the heart of Osiris [Ani] 1 His soul stands as a witness concerning him, his character is just by the great balances. No sin of his has been found." The Nine Gods of the Ennead at once respond: "⌈How good⌉ it is, this which comes forth from thy just mouth. Osiris Ani, the justified, witnesses. There is no sin of his, there is no evil of his with us. The Devouress shall not be given power over him. Let there be given to him the bread that cometh forth before Osiris, the domain that abideth in the field of offerings, like the Followers of Horus."

Having thus received a favorable verdict, the fortunate Ani is led forward by "Horus, son of Isis," who presents him to Osiris, at the same time saying: "I come to thee, Wennofer; I bring to thee Osiris Ani. His righteous heart comes forth from the balances and he has no sin in the sight of any god or goddess. Thoth has judged him in writing; the Nine Gods have spoken concerning him a very just testimony. Let there be given to him the bread and beer that come forth before Osiris-Wennofer like the Followers of Horus." With his hand in that of Horus, Ani then addresses Osiris: "Lo, I am before thee, Lord of the West. There is no sin in my body. I have not spoken a lie knowingly nor (if so) was there a second time. Let me be like the favorites who are in thy following." 1 Thereupon he kneels before the great god, and as he presents a table of offerings is received into his kingdom.

These three accounts of the judgment, in spite of the grotesque appurtenances with which the priests of the time have embellished them, are not without impressiveness even to the modern beholder as he contemplates these rolls of three thousand five hundred years ago, and realizes that these scenes are the graphic expression of the same moral consciousness, of the same admonishing voice within, to which we still feel ourselves amenable. Ani importunes his heart not to betray him, and his cry finds an echo down all the ages in such words as those of Richard:

"My conscience hath a thousand several tongues,

And every tongue brings in a several tale,

And every tale condemns me for a villain."

The Egyptian heard the same voice, feared it, and endeavored to silence it. He strove to still the voice of the heart; he did not yet confess, but insistently maintained his innocence. The next step in his higher development was humbly to disclose the consciousness of guilt to his god. That step he later took. But another force intervened and greatly hampered the complete emancipation of his conscience. There can be no doubt that this Osirian judgment thus graphically portrayed and the universal reverence for Osiris in the Empire had much to do with spreading the belief in moral responsibility beyond the grave, and in giving general currency to those ideas of the supreme value of moral worthiness which we have seen among the moralists and social philosophers of the Pharaoh's court several centuries earlier, in the Feudal Age. The Osiris faith had thus become a great power for righteousness among the people. While the Osirian destiny was open to all, nevertheless all must prove themselves morally acceptable to him.

Had the priests left the matter thus, all would have been well. Unhappily, however, the development of belief in the efficacy of magic in the next world continued. All material blessings, as we have seen, might infallibly be attained by the use of the proper charm. Even the less tangible mental equipment, the "heart," meaning the understanding, might also be restored by magical agencies.

It was inevitable that the priests should now take the momentous step of permitting such agencies to enter also the world of moral values. Magic might become an agent for moral ends. The Book of the Dead is chiefly a book of magical charms, and the section pertaining to the judgment did not continue to remain an exception. The poignant words addressed by Ani to his heart as it was weighed in the balances, "O my heart, rise not up against me as a witness," were now written upon a stone image of the sacred beetle, the scarabeus, and placed over the heart as a mandate of magical potency preventing the heart from betraying the character of the deceased. The words of this charm became a chapter of the Book of the Dead, where they bore the title, "Chapter of Preventing that the Heart of a Man Oppose Him in the Nether World." 1 The scenes of the judgment and the text of the Declaration of Innocence were multiplied on rolls by the scribes and sold to all the people. In these copies the places for the name of the deceased were left vacant, and the purchaser filled in the blanks after he had secured the document. The words of the verdict, declaring the deceased had successfully met the judgment and acquitting him of evil, were not lacking in any of these rolls. Any citizen whatever the character of his life might thus secure from the scribes a certificate declaring that Blank was a righteous man before it was known who Blank would be. He might even obtain a formulary so mighty that the Sun-god, as the real power behind the judgment, would be cast down from heaven into the Nile, if he did not bring forth the deceased fully justified before his court. 2 Thus the earliest moral development which we can trace in the ancient East was suddenly arrested, or at least seriously checked, by the detestable devices of a corrupt priesthood eager for gain.