Masonic Stories

The Morgan Affair

Who was William Morgan and why did he disappear?

The events that came to be known as the “Morgan Affair” sparked a panic in the United States when William Morgan mysteriously disappeared. The conspiracy theories surrounding his possible murder set off an anti-Masonic witch hunt that changed the political and social fabric of the United States. The ramifications of this pivotal event in American history forever altered Freemasonry.

William Morgan was a controversial figure in New York in the early 19th Century. His early life is largely unknown to history and many of the claims made about his life and character were so hotly disputed by his contemporaries that historians have been unable to sort fact from fiction.

He was born in 1774 in Culpeper, Virginia and claimed to have served in the war of 1812 as a Captain in the Virginia Militia. Though there were several men named William Morgan on the rolls of the militia at that time, none served with the rank of Captain.

After the war, he married a woman 25 years his junior and established a brewery that would later burn down. This loss reduced the Morgan family to absolute poverty, and he struggled to provide by working as a bricklayer and stonecutter in his new home of Batavia, New York. The situation wasn’t helped by what local histories of the 19th Century describe as Morgan’s propensity for heavy drinking and gambling. During his time in Batavia, Morgan made many fantastic claims about his wartime exploits and was known for boasting of his accomplishments at the local taverns.

One claim he made was that he had been initiated into Freemasonry. Thousands of Masonic historians have combed through the records, but no one can find any document to suggest he was ever initiated, passed or raised. It is known, however, that he was given the Royal Arch degree, on May 31st, 1825 at the Western Star Chapter #33, in Le Roy, New York after having given his word under oath that he had regularly received the previous six degrees. This, and the knowledge of Masonic ritual displayed in his expose, is the only solid evidence of his membership in Freemasonry.

In late 1825, after receiving the Royal Arch degree, Morgan attempted to visit lodges in and around his home of Batavia, New York. He was, however, denied entry into and participation in the ritual workings of these Lodges, as many of the members disapproved of his behavior and character. Known to locals as a drunk and a teller of tall tales, the truth of his Masonic status was disputed, and Morgan was turned away from the doors of Lodge after Lodge.

Shortly after, on March 13, 1826, Morgan announced that the publisher of the local newspaper had paid him a sizable sum of money to begin writing an expose on the Craft. The newspaper publisher, David Cade Miller, had himself received the First Degree of Freemasonry but had been prevented from advancing due to his poor reputation and conduct within the Lodge. These two disgruntled men, prevented from learning the secrets of Masonry by their own personal shortcomings, hatched a plot to extort what little they had learned for personal gain. In doing so, they broke their solemn obligation not to reveal the mysteries of Freemasonry.

Almost immediately, the local Masons of Batavia learned of this endeavor. A notorious alcoholic, Morgan would visit the local taverns every night and brag about his progress. In 1826, Freemasonry played a much greater role in the social and political life of America. Many local politicians and influential men were Freemasons and such flagrant violations of Masonic secrecy in a small community like Batavia could not go unnoticed.

The members of Batavia's Masonic Lodges immediately began to search for methods by which to preserve the sanctity of Masonic secrecy. They placed an advertisement in the local newspaper denouncing Morgan and his expose and an attempt was made to burn down David Cade Miller's printing press. As many local policemen and judges were also Freemasons, they looked to the legal system to prevent Morgan from finishing his work.

On September 11th, 1826, he was arrested for theft and the nonpayment of a loan and imprisoned in a local jail. His collaborators, newspaper owner David Miller included, paid his bond and secured his release. Soon after, Morgan was again arrested for an unpaid debt, and, after having been in jail for only a day, was whisked away in the night by a group of unknown men and was never seen again.

Immediately rumors began to fly as to his whereabouts and his fate. Had he been killed? Perhaps exiled into Canada? He had been taken to jail by a mob of Freemasons, and there were many witnesses to the fact that he was also removed from his cell by Masons which immediately began to fan the flames of conspiracy.

Anti-Masonic sentiment quickly began to take root and grew as time passed and no sign of William Morgan could be found. A recession had struck shortly after the conclusion of the War of 1812 and many Americans found themselves out of work. As Freemasons tended to be wealthier members of society, conspiracy theories claiming that Freemasons were running the country to their own benefit, at the expense of the people and their new democracy, began to spread.

Morgan’s expose was published soon after his disappearance by his collaborators. The mystery and intrigue surrounding the work attracted publicity and interest and it soon became a national bestseller. The Governor of New York, himself a Freemason, offered a $1,000 reward for information about what had happened to Morgan, and the attention of the young republic was consumed by the fate of William Morgan.

But what did happen to William Morgan? Historians, both Masonic and not, have attempted to determine the truth of the events with little success. Reverend Charles Finney in his book The Character, Claims and Practical Workings of Freemasonry published 1869 recounts the tale of the confession allegedly given by the murderer himself, Henry L. Valance, who apparently drowned Morgan in the Niagara river with the help of two accomplices. In the book Low Twelve, published in 1907, it was claimed that Morgan was paid $500 to leave town for good. Some say he went to Albany, others to Canada and still others claim that he fled to the Cayman Islands, where he would eventually be hanged for piracy.

As the hysteria continued to mount and the accusations of conspiracy reached a fever pitch, a decomposing corpse was found on the shores of Lake Ontario not far from where Morgan was rumored to have disappeared. Was this the body of William Morgan? His widow initially claimed that it was but when the wife of missing Canadian man Timothy Munroe came forward and claimed the cadaver was clothed with the exact garments her husband was wearing when he disappeared, the discovery was passed over. It would not be the first time his body would be “discovered.”

In 1881, 55 years later, in a quarry near Albany, New York, a skeleton was found which reinvigorated the conspiracy theories surrounding the disappearance and alleged murder. Several artifacts engraved with the initials W.M. were found near this skeleton and some proponents of the Masonic murder theory have insisted that this discovery was in fact the long-lost remains of William Morgan. However, this discovery was made just after the National Christian Association commissioned a statue to commemorate Morgan’s martyrdom “to the freedom of writing, printing and speaking the truth” and many wished to revitalize the conspiracy theories surrounding Morgan’s disappearance.

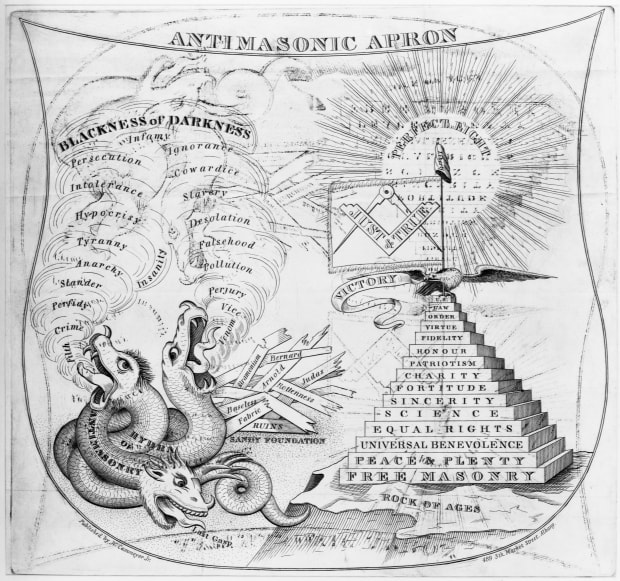

Perhaps the longest lasting effect of the Morgan Affair was the formation of the Anti-Masonic Party, America’s first third political party and a major force in American politics for a short time after William Morgan’s disappearance. Spurred on by the public outcry raised by the events of the Morgan Affair, the Anti-Masonic party had only one goal: to ban all secret societies, especially the Freemasons, from American public life.

For years Freemasonry had played a very public role in American politics and the President elected shortly after the Morgan Affair was Andrew Jackson, a prominent Freemason. The Anti-Masonic Party galvanized itself around a message of anti-elitism and anti-corruption and sought to unseat Jackson and Freemasonry in general from American politics both at the local and federal level.

In the midst of this strong anti-Masonic sentiment, membership in the Craft declined considerably. Exact numbers are unknown but during this time hundreds of Lodges closed, thousands of members resigned, and Freemasonry in the United States was thrown into crisis. Many of the most experienced Masons were pressured to leave by their families and communities. Some of the greatest Masonic minds of a generation were lost and their symbolic knowledge and the ritualistic experience they possessed was lost with them

The Grand Lodges of the United States, in order to preserve Masonry against what they considered an attack of ignorance and superstition, initially tried to determine Morgan’s fate and punish whatever conspirator’s may have existed, with many prominent Masons offering rewards for information as to his whereabouts. Despite these efforts, it soon became clear that, in order for Masonry to continue to attract new members and avoid persecution, a change of course was needed.

In 1839, the Grand Lodge of Alabama called for all Grand Lodges in the United States to meet in Washington D.C. to address the mutual problems that had been brought on by the sordid mess of the Morgan Affair. This was the first time in history such a convention was called, and it was a sign of the magnitude of the crisis that it was deemed necessary. The first attempt to convene the Grand Lodges only attracted ten of them. The second attempt brought together sixteen Grand Lodges and was held on May 8th, 1843 in Baltimore, Maryland. They met to discuss the future of Freemasonry in America and how the Craft would respond to the catastrophe created by the disappearance of William Morgan.

What they would decide at this convention and the reaction afterwards would have a profound impact on American Freemasonry and would alter the Craft forever. Prior to the convention, there was little in the way of standardized ritual and esoteric teachings were more prevalent. It was slowly realized that these elements damaged the public perception of the organization and would have to be toned down or eliminated altogether in order to appease the public and restore interest and membership in the Fraternity. The occult principles of Freemasonry would have to be suppressed to placate the Christians caught up in the revivalism of the Second Great Awakening.

This resulted in American Freemasonry moving away from its more esoteric and symbolic roots and emphasizing the fraternal nature of the Brotherhood. From this day forward Freemasonry would slowly evolve into a charitable organization rather than a true Mystery School. Music began to fade from its ceremonies, Masonic Temples began to be known as “halls” and education was replaced with fundraising. The standards of proficiency were diluted, and important Masonic symbols began to disappear. Within a generation, the Lodges of the Enlightenment had been replaced with social clubs and charities.

The events of the Morgan affair faded from memory and the public quickly forgot their anti-Masonic fervor. However, no modern Masonic conspiracy theory will ever compare to the zealous political activism and near extinction of the craft created by the disappearance of William Morgan. The ramifications of Morgan’s disappearance continue to affect the Craft to this day. Some claim that the reactionary changes made in the wake of the Morgan Affair saved Freemasonry from being completely destroyed. However, others believe that Freemasonry sold its soul in exchange for public acceptance. While membership did once more increase, the essence of Freemasonry was lost, until time or circumstances can restore the genuine spirit of the Craft.